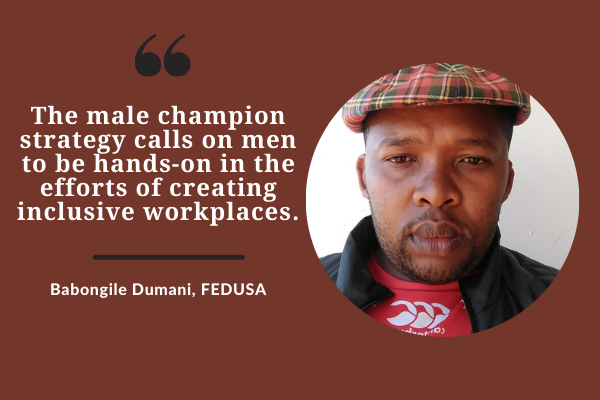

Why did you become a male champion in the LRS/ILO Young Women Leadership Development Programme (WLDP)?

I work in the Training and Development portfolio of the Federation of Unions of South Africa (FEDUSA). FEDUSA is the second-largest union federation in South Africa, with a membership of about 21 trade unions representing close to 600,000 workers. Our Training and Development portfolio focuses on young workers and looks at trends in key areas that we think are problematic, such as climate change, gender inequality and Gender-Based Violence (GBV).

I joined the LRS/ILO

Young Women Leadership Development Programme (YWLDP) in 2017, together with other young male worker leaders in trade union federations in the SADC region. At that time I was the general secretary of young workers at FEDUSA. The male champion strategy calls on men to be hands-on and to push the envelope about gender equality in workplaces.

In May of 2017, comrades met in eSwatini to launch the programme. The choice of the meeting venue was very deliberate – the conditions for workers are poor and unions in the Kingdom struggle to organise properly due to specific challenges. We left the meeting with a firm grasp of the programme’s objectives and also convinced that patriarchy (and gender-based violence) is real and occurs in all forms and spaces. These issues aren’t inherent in our genetic make-up. We are socialized to behave this way and a shift in attitudes is needed urgently. At a personal level, I experienced an awakening that’s making some impact at FEDUSA and in my work.

Tell us more about the impact of the male champions programme at FEDUSA?

FEDUSA tasked us with designing a plan of action based on what we learned from this project, which is supported by the Labour Research Service and ILO. The plan of action specified the things we’d do within our spaces to achieve gender equality and address gender-based violence. However, we were responding to the political climate at that time and the opportunities that were available then. That status quo would change. Four months after the eSwatini meeting, FEDUSA was invited by the government to take part in the implementation of the National Youth Policy. Consequently, a different opportunity presented itself and we decided to change tack about our gender equality plan and how it’d be implemented. We wanted the plan to find expression beyond the trade union/workers space.

The Labour Relations Act defines trade unions as worker-led organisations. Ideally, this means that we are restricted to operate in the labour space. But, we took a decision not to confine ourselves to the union space because patriarchy is a social norm that’s difficult to change and requires that we reach as many men as possible, considering that they the main catalysts or vehicles of the norm. We thought we’d make more impact if we could penetrate, for instance, government-led spaces, through influencing policy.

Through the National Youth Policy platform, FEDUSA was exposed to males of between ages 14 and 15. Essentially, we had a better chance of addressing patriarchy and gender discrimination if we could access workers at a younger age. The youth policy platform (where I represent FEDUSA) handed us that.

We are pushing for relevant gender programmes, as well as Love Life – the popular youth leadership, life skills and sexuality awareness programme. Such programmes can advance the struggles facing women in society and guide how we engage young people now and in the future.

At the BRICS Youth Summit in July 2018, I urged the participants from member countries to put women’s rights on top of their agenda. We advocated the concept of male champions and how it could find expression in BRICS. Patriarchy and gender inequality are also widespread in China, India and Brazil. Women are abused and socialised to view it as the norm. Within BRICS, GBV and patriarchy are related to the high levels of unemployment and lack of access to business opportunities for many women. We’ll constantly ensure that this platform addresses gender inequality in all spaces, from agriculture and mining to the education and healthcare sectors. Statistics show patriarchy and GBV find less expression when women are educated, employed and independent.

When did you become aware of gender inequality?

I grew up in a middle-class and patriarchal family in Eastern Cape Province. I was taught that men acted in a particular way. I was supposed to have the demeanour of the protector of the house. I interacted with my sisters in a certain way, for instance, I didn’t cook and clean because that was done by my sisters. My job was to work in the veld and see to our cattle. I was socialised to behave in a way that perpetuates patriarchy. I became fully aware of gender inequality when I joined the union and participated in LRS and ILO training.

Many young women are joining trade unions but get disillusioned because we haven’t implemented our gender policies effectively. Women struggles in unions aren’t prioritised as they should be. We can see it in the poor representation in bargaining forums and in leadership positions.

LRS research also shows that the CEOs are mainly men. I know many qualified women in company structures that are relegated to lesser roles – serving men so that the men can ‘sit properly’ in boardrooms. The good thing is we’ve diagnosed what the problem is and are taking corrective measures, albeit too slowly.

The training offered by the YWLD/male champions programme helped me to understand the root cause of patriarchy and how we can address it in the union, at workplaces and home settings. I have taken the responsibility of creating spaces for sharing what I have learned with our affiliates and within the federation structures, with a view of developing appropriate responses.

How do your friends view your role as a gender male champion?

It’s quite difficult because some men are very resistant to change and are of the view that this is all about women and has nothing to do with them. A few times people have walked out of a meeting when I start engaging with them about gender issues such as the runaway rape cases in our society. I have learned some different approaches to remedy that, for instance, researching my target audience so that I can adopt the appropriate language and posture. My audience comprised of male workers between the ages of 34 to 54 will likely have a girl-child like I do, and would be open to the idea of prioritising buying sanitary pads over another less important product. Many girls miss roughly 80 days of the school year because their fathers thought buying pads isn’t a priority. The pads issue can also be a gender discrimination issue and I believe a great entry point to the inequality debate among some audiences. We are dealing with human minds that are hard-wired to resist social norms change. It takes using effective processes and strategy to avoid isolating the very people you want to change.