Community Health Workers form the backbone of South Africa’s primary healthcare system. They link clinics with communities, providing vital services in areas others cannot reach. Yet they remain on the periphery – poorly paid, insecurely employed, and lacking the recognition given to other health professionals. The South African Care Workers Forum (SACWF) is dedicated to changing that.

Formed by Community Health Workers, SACWF is part of the Labour Research Service (LRS) initiative, Transforming Public Care Work Programmes in South Africa. We bring together care workers in public care programmes, including Community Health Workers, Volunteer Food Handlers, and Early Childhood Development practitioners, to advocate for equitable public care policies.

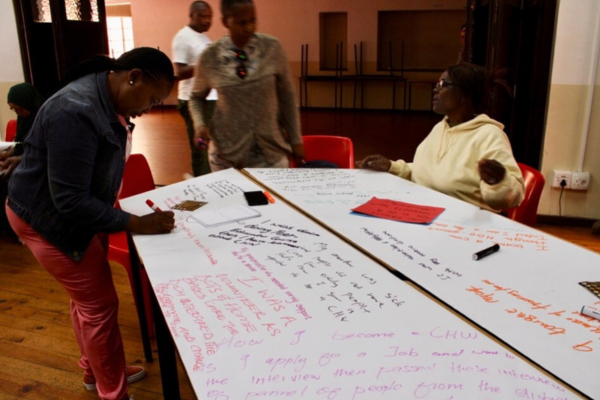

In March, Community Health Workers from different provinces met at Community House in Cape Town, facilitated by LRS, to share stories that revealed the scope and complexity of their work.

March 2024, Community House, Cape Town: LRS supported 65 Community Health Workers to generate evidence and strategies for valuing care work by voicing their life struggles and situated knowledge as care workers, activists, women and breadwinners.

“We are holding many feelings - long-standing pain, strength, pride, and anxiety.”

— Community Health Workers at LRS/SACWF workshop

“It is Ramadan, a month of sacrifice. We are sacrificing, but is it worth it? I’m thinking about the comrades that have fallen, who have walked the road with me but have lost. How many comrades are we going to lose? My heart and thoughts are heavy.”

— Salaama, Community Health Worker with 13 years of experience

Care work, they explained, is more than a job: “Care work is in our hearts. No one will fight except us.”

“It’s not true that we came from nowhere with no skills.”

Community Health Workers reject the notion that they entered the profession empty-handed. Some applied directly, others came through volunteering or years of caring for relatives and neighbours. Some care workers had formal training, while many were self-taught. They recognise they were already doing the work – palliative care, tube feeding, or basic nursing – long before they were recruited. Some pointed to Grade 12 as the qualification that opened the door.

When asked to explain their work to someone from another planet, one worker said:

“We offer support. We are counsellors, social workers, nurses, cleaners, all in one.”

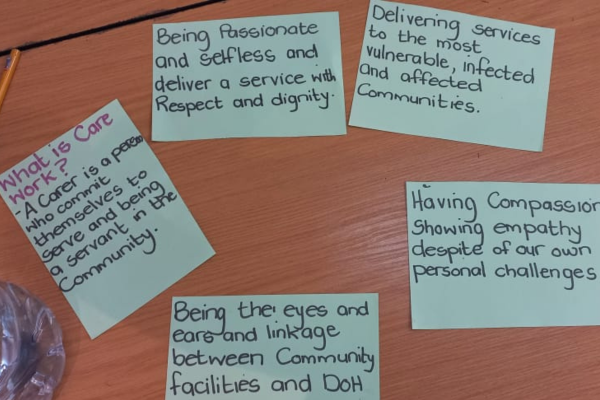

What “support” means for Community Health Workers

- Practical: Feeding, exercise, bathing

- Emotional: Comfort, companionship and reassurance

- Psychosocial: Helping patients cope with illness

- Healthcare: Monitoring vitals, supporting treatment, ensuring adherence

- Social: Linking patients to clinics, ambulances, or social services

- School health: Addressing various topics, including the use of sanitary pads and condoms

- Disability support: Facilitating physiotherapy and disability grants

- Referrals: Identifying broader social issues and connecting patients to services.

Community Health Workers at the LRS workshop increased critical analysis of their understanding of care work and what gives it value.

This dedication comes at a cost.

“Patients think the extra mile we go is mandatory. It is not. We tolerated it and gave away our power by doing what we do out of love, so we absorb everything that comes with it.” — Community Health Worker.

— Community Health Worker

Systemic and gendered inequities

Community Health Workers’ struggles are rooted in how society perceives paid care work. Women care workers are expected to perform the most demanding physical and emotional tasks, while men work in administrative or public-facing roles.

“Without us, communities would fall apart. The primary healthcare system would collapse. Our work holds households and communities together, yet when we advocate for our rights, people accuse us of not caring.”

— Community Health Worker

Even within the workforce, gender roles shape responsibilities.

Women carry the burden of hands-on care, which reflects broader patriarchal norms in government and NGO spaces. Men refuse certain intimate care tasks and prefer administrative or public-facing roles. A male Community Health Worker reflects:

“How I became a Community Health Worker was influenced by how I saw my father treat my mother. My children are surprised when I cook at home because it seems abnormal. In my role, I drive patients to clinics. When I ask female colleagues why they don’t do this, they say it’s men’s work.”

— Community Health Worker

For SACWF, achieving recognition and dignity means challenging both state neglect and entrenched gender hierarchies.

The Genesis of the SACWF through the eyes of Community Health Workers

Bulelwa’s story

SACWF emerged from the determination of Community Health Workers. Care workers envisioned a safe space to mobilise and organise on their terms.

Bulelwa’s recollection begins in Mdantsane, Eastern Cape, before the SACWF was formed. Care workers from both private and public health facilities began meeting every Wednesday evening in a small office at a taxi rank.

“We squeezed into a small office at a taxi rank every Wednesday evening. We didn’t have a name, but we knew we had to do something about our challenges.”

— Bulewa, Community Health Worker in the Eastern Cape (over 20 years of service)

The Wellness Foundation (formerly AIDS Response) played a formative ‘mother body’ role for SACWF.

“They run the Diapela Programme, which supported caregivers through workshops we call 'share shops'. We got the tools for stress relief and mutual support. You could cough out what was happening to you."

— Bulewa, Community Health Worker in the Eastern Cape (over 20 years of service)

A leader from the Eastern Cape group visited Cape Town, meeting the Wellness Foundation and the People’s Health Movement. Inspired, five Community Health Workers attended an Indaba and an assembly at the University of Cape Town, where the idea for a care worker forum was born. That ‘forum’ name choice was practical and political.

We needed a space outside of the traditional spaces to discuss our challenges. We are the ones who know the challenges we face. SACWF is all about us.”

The Diapela programme trained 20 Community Health Workers in the Eastern Cape, creating a core group to “care for carers,” and workshops spread across the Eastern, Northern, and Western Cape.

“We pumped the energy from the workshops to recruit everywhere. We spoke about the forum. The people were so keen.”

They introduced themselves in district health offices as the Community Care Workers Forum, offering half-day debriefings that doubled as organising spaces.

“The managers were excited. Even the director was happy that the programme was helping care workers… But they did not know that we also used the sessions to organise and access our rights. At this stage, we used the country’s constitution to speak about our rights as we were not yet equipped in labour law.”

The Forum approached the labour department, which provided training in the Eastern and Northern Cape. A chance encounter at a Workers World Media Productions event connected them to NEHAWU in the Free State, leading to a gathering for Community Care Workers.

“The hall was full of care workers – lucky for us, he also invited the Department of Labour and care workers were able to ask questions at the meeting.”

Regular workshops at the Wellness Foundation in Cape Town produced forum policies and a constitution. The forum aligned with the Treatment Action Campaign to learn about the Bill of Health and built alliances with the People’s Health Movement and Workers World Media Productions.

On 9 August 2015, the forum held its first national assembly, elected leaders, and changed its name to SACWF to include facility care workers, establishing trust among previously reluctant members.

“We created a charter of demands and distributed leadership roles across provinces. However, we faced challenges as the forum grew; many organisations offered funding, while others questioned why we remained a forum instead of forming a trade union.”

Tensions about forming a trade union escalated at a national meeting convened by Workers World Media Productions. SACWF chose to remain a forum, but divisions widened. The Wellness Foundation set up a rival leadership, and the forum nearly collapsed. But the rival groups eventually attempted to reunite.

“The saddest part of all of this is that after we met, the Wellness Foundation shut down. We were left with no funding. We were leaning on a wall that was about to collapse.”

Rozette’s story: Building the forum’s collective memory

Rozette, SACWF member in the Western Cape.

Rozette from the Western Cape traces the forum’s roots to Aids Response (Wellness Foundation), which gave Community Health Workers a space to share challenges and find support. Retreats built confidence but also drew backlash from managers who tried to block participation and victimised workers. Rozette remembers drafting the forum constitution and demands with comrades during the night.

Care workers connected with the Bargaining Council, Khanya College, Black Sash, and Section 27. They held Indabas, produced a comic booklet telling their story, and travelled, often with little resources, to make their voices heard.

“We gave our days and our time, even when we had no money and no place to sleep. I remember gate-crashing a meeting in Braamfontein. The decision makers found out we were from the Western Cape. In the breakaway groups, we realised our issues were the same. The struggle was real, and what happened in Johannesburg made us strong.”

Organising in the Western Cape was risky. Many CHWs faced victimisation, and Rozette nearly lost her job.

Siphokazi: The Story of the Tree

Siphokazi recalls her first workshop in Nelson Mandela Bay, when care workers were unorganised:

“We were debriefing and drawing on big sheets. It felt like a game, but out of that came the SACWF tree logo on our T-shirts. When you see the tree, its roots run deep underground. To uproot it, you would have to go all the way down. That is how we see carers. We are fighting, we are struggling, but no one can uproot us. This work is for future generations, and to destroy what we have planted, you would have to go very deep.”

Media training with Workers World Media Productions and leadership sessions at Khanya College helped them communicate effectively and lead fellow carers. There were some hard times. In Umtata, the forum ran out of funds, and hope seemed lost. The leaves of the tree were falling.

Renewal came through a People’s Health Movement forum and reconnecting with Bulelwa after many years.

“I could sense the dryness. The leaves came back at the People’s Health Movement forum. We came back together, and there were important moments. Buli said the forum is still there, and that I must join and revive other carers. Last year, we helped carers to fill in forms for the legal case about wanting to be made permanent.”

Salaama: as a relative newcomer

Salaama, a newer member of SACWF, lauds the groundwork laid by earlier organisers.

“Carers met in any available space, even without money. To hear the story from the beginning can be painful. We need to continue discussing this story."

Core struggles of Community Health Workers

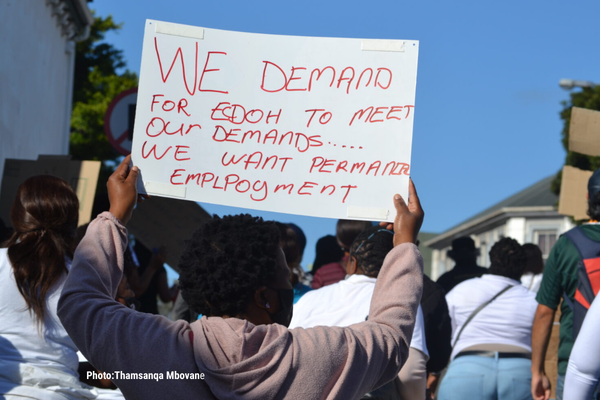

1) Labour court judgement on permanent employment

In January 2025, the Johannesburg Labour Court ruled that community health workers must be deemed permanent government employees. The case was brought by NEHAWU, which successfully overturned a 2021 bargaining council decision that allowed recurring fixed-term contracts based on Treasury “external funding.” Acting Judge Ashley Cook found Treasury funds were not external, making the contracts indefinite under the Labour Relations Act. The ruling is a major victory in Community Health Workers’ struggle for job security and benefits, yet uncertainty remains.

With the health department’s promise to slate 27,000 of 55,000 for permanent employment, Community Health Workers ask: Who decides who gets in? Who gets what stipend amounts? What about care workers tied to NGOs? What about those with decades of experience but no matric certificate? What happens to older Community Health Workers approaching retirement after a lifetime of service?

“A victory for some cannot become a punishment for the rest.”

— SACWF member

2) Western Cape: Trapped in the NGO model

Community Health Workers in the Western Cape are contracted through NGOs, not the Department of Health – a form of labour broking that leaves them vulnerable. Contracts depend on short funding cycles, with no guarantees of continuity or pensions. SACWF is strategising to challenge this model by advocating for direct inclusion on the government payroll (PERSAL).

The power of storytelling: Care workers use stories to disrupt systems that devalue care work

“In the Western Cape, we work for NGOs. I don’t know if I will still have a job.” Nobuntu

– (13 years working as a Community Health Worker)

“I am almost at the age of retirement, and yet, I am not acknowledged. When I retire, I will leave with no recognition or acknowledgement, no money. Only the pay I get for the month.

– Suzette (34 Years working as a Community Health Worker)

3) Eastern Cape: Stipends and deductions

For Community Health Workers in the Eastern Cape, dignity starts with pay. In several districts, workers went three months without stipends and got no explanation from the provincial health department. After a sustained, non-violent push led by SACWF, from clinics to district offices to the MEC, the money was finally released.

Relief didn’t last. A new circular alleged “overpayments” and ordered clawbacks.

“My stipend went up from R4,800 in 2024 to R5,288 in 2025. Now they say it will be reversed to R4,800, and they’ll deduct the difference from what we earn next.”

– Bulelwa, Community Health Worker

Labour experts say the deductions are unlawful, citing the Public Service Act, which bars unilateral salary cuts. Stipend levels also differ by province, with no transparency on how budgets are set. For many workers, the patchwork reinforces a sense of contempt.

SACWF’s principles in action

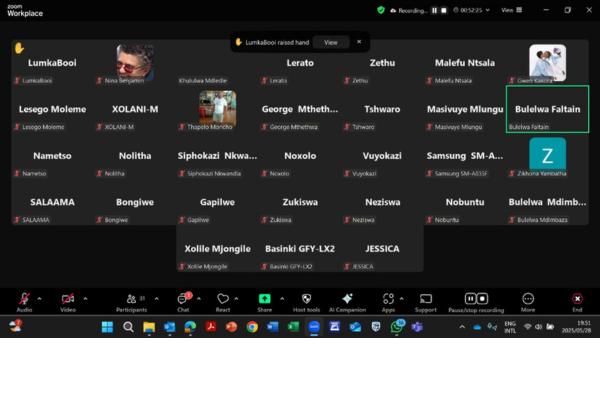

LRS hosts bi-monthly online meetings with SACWF members to sustain connection and learning. Care workers receive a data stipend from LRS to support their participation in the 90-minute Thursday sessions.

In May, SACWF set out guidelines for recruitment.

- Nothing about us without us

- Telling the truth — no false promises

- Valuing care work

- Speaking out to make work visible

- Empowering each other

- Embracing all identities

In recent months, Community Health Workers faced unpaid stipends, threats to job security, sudden transfers, and being ignored by authorities. Divisions emerged across provinces and even within facilities. Many struggled to support their families while keeping the forum strong. LRS facilitated a space for Community Health Workers to reflect on how the SACWF principles guided their actions regarding the Eastern Cape stipends issue. Solidarity, accountability, persistence, and dignity emerged as key to their approach.

“The one slogan that always stands out for me: injury to one is an injury to all. I need to serve with dignity and demand change by treating others with respect,” one Community Health Worker said, highlighting the core of solidarity.

Accountability was vital. “Sometimes you hear something, but then you’re not sure about it. Then it’s my job to go look for answers… Holding leadership, including myself, accountable. We can’t call for justice outside if we don’t practice it from the inside.”

Community Health Workers emphasised strategic organising. “If you start with the MEC office, you have not built up support… along the way, you can create allies in the different offices, allies that can assist you later.”

Persistence and non-violence shaped their approach. “We stood our ground… we stayed calm, we built relationships, we stood for ourselves and did not depend on the union, and we did not make promises to our comrades that we could not keep.”

Dignity under pressure was a guiding principle throughout. “That word dignity keeps coming to mind… I was so angry thinking, how can the department do this? And to hear how you handled it, to see the kind of vision staying with all the principles as part of your practice, teaches us so much about organising.”

Conclusion

The struggle in the Eastern Cape showed SACWF’s power in principled, non-violent organising. Care workers secured overdue stipends without risking jobs or resorting to destructive tactics.

“By using nonviolent approaches, by speaking that truth, by staying connected and working with respect, you are changing the existing narrative where you can only win a struggle by destroying other people and property.” – LRS facilitator.

The task now is to embed SACWF’s principles in daily practice so that every Community Health Worker experiences the forum’s vision at the head, heart and feet levels.

RELATED ARTICLE

The LRS Decent Work: Transforming Public Care Work Programmes in South Africa initiative is supported by the SAGE Fund.