48 Volunteer Food Handlers in Gauteng met on 21 June at the second Thinking Laboratory hosted by the Labour Research Service (LRS) to deepen their understanding of public budgeting, challenge narratives, and create advocacy strategies. This engagement builds on our first Thinking Laboratory in June, where Volunteer Food Handlers explored how budgeting at home and on a national level reflects power and priorities.

What is an LRS Thinking Laboratory?

A Thinking Laboratory is a space for collective inquiry and agency, using a range of participatory feminist popular education methods. Feminist popular education is about actively constructing knowledge through dialogue and reflection. We work with Singleton’s “head, heart, and hands” model for transformative learning.

- Head: Strengthen understanding of systems that shape budgeting in care work.

- Heart: Build confidence and solidarity through shared experience and reflection.

- Feet: Support concrete action to claim rights and shape public care programmes policies.

LRS uses ordinary language, movement, music, art, debate and food to build an environment where participants feel confident to speak and safe to imagine alternatives.

Volunteer Food Handlers participating in the series of LRS Thinking Laboratories experiment with gender-responsive budgeting by exploring the 2025 National Budget and examining what is missing from the budget of the National School Nutrition Programme, a public care programme run by the Department of Basic Education. Volunteer Food Handlers share experiences, debate ideas, and develop practical recommendations, from what decent work should look like to how the National School Nutrition Programme can support food sovereignty and a care economy. Insights from these spaces feed into our ongoing engagement with the Department of Basic Education.

HEAD: A critical analysis of the NSNP budget at a school level

What does the NSNP budget look like at the workplace, i.e. the school?

Volunteer Food Handlers recapped the “percentages game” introduced in the first Thinking Laboratory. Women moved around the room, forming groups of 100%, 50%, 25%, and 10%, giving physical meaning to abstract concepts.

“It makes more sense now when they say ‘only 1% of the basic education department budget goes to the National School Nutrition Programme'."

Volunteer Food Handler

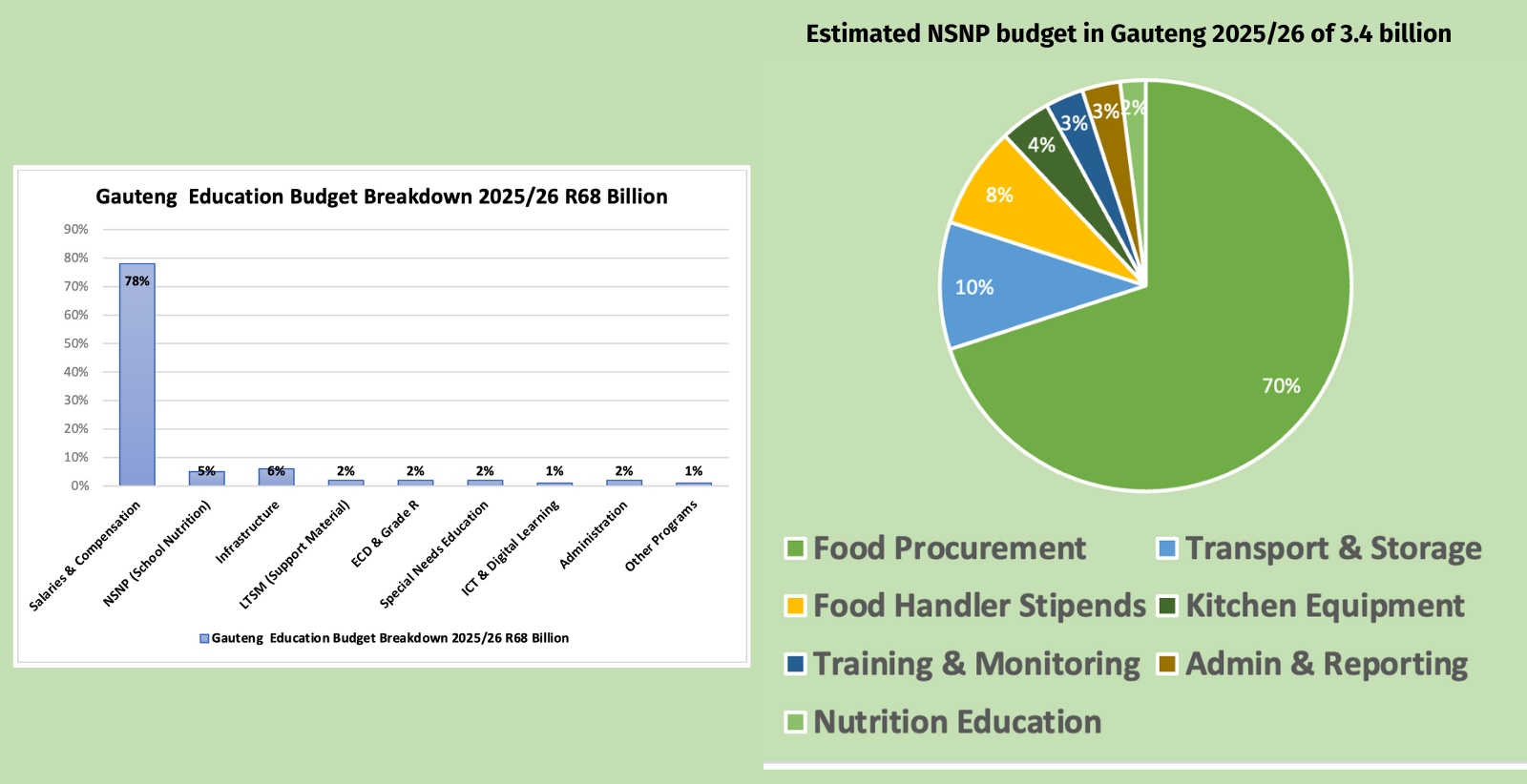

A bar chart showing the Gauteng education budget (R68 billion) and a pie chart showing the National School Nutrition Programme’s share (5%) made the gap visible between what the programme promises and what it delivers.

What is missing from the budget?

In small groups, Volunteer Food Handlers identified what is missing from the National School Nutrition Programme budget, based on their daily realities in school kitchens. Even the items that appear in the budget often do not reach the school kitchens:

“We don’t have storage...we use classrooms...then the rats eat the food, and we get blamed for stealing. We bring our knives and pots. No one trains us, they think because we are women, we know how to cook. There’s no administrative structure and support...if something goes wrong, we don’t know who to report to. We don't have formal recognition - no payslips and certificates...when our contracts end, we have nothing to show that we have worked. Ceilings are falling in our kitchens...they say occupational health and safety is in the budget, but where? Our salaries should increase since we do some of the work that is supposedly done in their budget."

Volunteer Food Handlers

What is inflation, and how does it impact a budget?

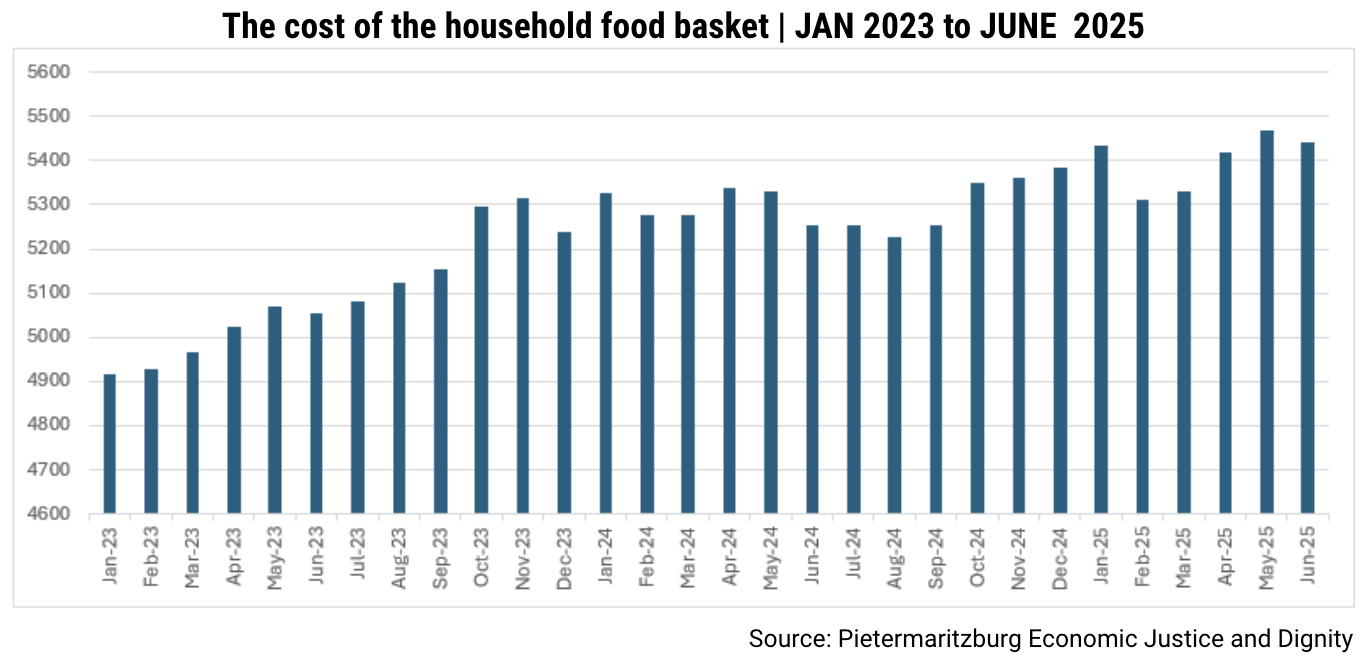

The Pietermaritzburg Economic Justice and Dignity Group’s food basket costs an average of R5 443,12 per month, far above what Volunteer Food Handlers earn.

The household food index is specifically designed to measure food price inflation as experienced by households living on low incomes in certain provinces, and can give insight into low-income households nationally.

A display of staple items from the Pietermaritzburg food basket, used to illustrate the recommended contents of a nutritious household food basket.

"We don’t earn enough to buy the items in the food basket. I haven’t had a full bottle of oil in my home in a very long time."

Volunteer Food Handler

The facilitator introduced inflation using a bar chart that showed the price of samp rising steeply over three years, an example of how the cost of basic food items continues to increase. At the same time, the stipends for Volunteer Food Handlers largely remain stagnant.

Inflation is a sustained rise in the general level of prices of goods and services. It is measured as an annual percentage increase, for example, from June 2024 to June 2025. A falling rate of inflation means that prices are rising more slowly. Food prices increased to 4,7% in June 2025 from 4,4% in May 2025.

Food handlers discussed why inflation happens and who benefits. Concepts such as demand and supply, speculation, government borrowing, imports and exports were introduced through discussion and analogy. The Volunteer Food Handlers made the connections. Inflation eats away at wages. Companies often raise prices simply because they can, particularly when it comes to essential goods.. The discussion also pushed back the stereotype that food handlers lack broader knowledge.

“We understand how the economy works. We feel it every day.”

Volunteer Food Handler

HEART: Volunteer food Handlers are curious, excited and confident

Thinking Laboratory 2 opened the space for emotions to emerge. There was dancing, singing, heated debates and laughter. Two children joined the session – a three-week-old baby and a lively seven-year-old boy who danced, sang, and settled in with the group. For some food handlers, this space was one they could access without having to choose between their child and their own development.

“We told the women they could bring their children. If we are serious about care work, we need to create spaces where care is part of how we organise.”

LRS facilitator

The group included younger and older women. The new, younger food handlers brought energy and confidence. Their presence encouraged older participants to speak more, while mentorship flowed both ways. The space became a kind of rehearsal: women could test their voice before using it in public.

“We know this budget. We know what is missing. We can say it.”

Volunteer Food Handlers

Confidence was also visible in the way women engaged with the budget charts. Compared to Thinking Laboratory 1, there was much more discussion, questioning, and proposal-making.

FEET: Taking action to create a budget that responds to the nutritional needs of learners and decent work for the Volunteer Food Handlers

The final activity focused on what Volunteer Food Handlers can do to raise the alarm about what is missing from the school budget. In different ways, they began to act like budget officers. They began reallocating the National School Nutrition Programme budget themselves. One group proposed cutting the training allocation.

"Why are other people getting money to train us, yet we can do the training ourselves, which we do? The money should be reallocated to our pay."

Volunteer Food Handler

In small groups, food handlers prepared to speak to three audiences: other Volunteer Food Handlers, National School Nutrition Programme school coordinators, and the broader school community, for example, parents.

- To NSNP school coordinators: “This work is challenging, and we need support. You should help us be heard and recognised. If we had proper tools and facilities, our work would be less stressful and easier to do.

- To other food handlers: “Stand up for your right to be seen, to be respected, to be recognised.”

- To parents: “This is what we go through every day. Help us raise our voices.”

Key outcomes

- Volunteer Food Handlers are now confident in using percentages and inflation to explain their realities.

- Volunteer Food Handlers can identify gaps in the national and provincial budgets and say why they matter.

- Volunteer Food Handlers view budgeting as a political process shaped by power and voice.

- Volunteer Food Handlers are developing campaigns to address deep-rooted inequalities that undervalue care work and limit national potential and prosperity.

RELATED ARTICLE

LRS Thinking Laboratory 1

What does the national budget say about how the government values care work?