A Women’s Day celebration by Volunteer Food Handlers in Gauteng on 9 August 2024. Volunteer Food Handlers address NSNP issues, food sovereignty, and better working conditions at LRS Power Up! feminist safe spaces, aiming to make their jobs visible, recognised, valued and remunerated.

Women’s Month should be a time for action, not just empty platitudes. It should prompt us to confront difficult issues, like the lack of recognition and value for care work performed by women. The experience of Volunteer Food Handlers in the National School Nutrition Programme (NSNP) highlights the issue of care work being undervalued and underpaid.

In 2024, the low value assigned to care work continues to justify precarious work conditions, inadequate pay, limited training, and inadequate social protection for Volunteer Food Handlers. This occurs despite the vital role of food handlers in the NSNP, which is crucial in improving school attendance and learning outcomes.

“We are not just the unseen ‘hands’ and ‘heart’ of the programme; we are essential players in creating a decolonised and socially just school food programme.”

Volunteer Food Handler, Gauteng

The perspectives of the food handlers challenge the dismissive public and institutional view that their work is low-skilled and of little value.

Over the past three years, a group of food handlers in Gauteng have used LRS feminist safe spaces to discuss their issues with the NSNP, promote food sovereignty in their communities, and organise for better working conditions.

The food handlers invoke the strength of imbokodo – the isiZulu word for “rock” – connecting their present struggles to those of the past. This concept, captured in the saying “Wathint’abafazi, wathint’imbokodo, uzakufa! Ubobhasopa!” (“You strike women, you strike a rock, you will be crushed! You should be careful!”), represents the collective power and resilience of women. It is strongly associated with the 1956 Women’s March, commemorated on Women’s Day. By invoking imbokodo, the food handlers honour the women who shaped them, acknowledging their roles in passing down values, skills, and resilience through generations.

Honouring their heroes

On Women’s Day, the food handlers reflected on their dual identities – as mothers, wives, and guardians in their private lives, and as workers in public spaces. The food handlers shared stories and totems representing their personal heroes:

On Women’s Day, the food handlers reflected on their dual identities – as mothers, wives, and guardians in their private lives, and as workers in public spaces. The food handlers shared stories and totems representing their personal heroes:

Khuli, a former food handler: “My grandmother, a domestic worker, was an outstanding cook known as the ‘black madam’ of the neighbourhood. She made even the simplest meals with love. I am an amazing cook because of her…Being in LRS spaces, interacting with food differently, and wearing an apron all remind me of her and the vital, spiritual role food plays.”

Thiwe, another former food handler, brought a traditional Pedi pot: “It keeps meals at the perfect temperature, whether hot or cold, much like a flask. My grandma raised me and taught me much of what I know today”.

Pat shared a butternut: “because it reminds me of my mother, who loved farming pumpkins…Every time I see a butternut, I think of her”.

Nomadlozi brought plates that connected her to her ancestors, and photos of her family: “I often felt invisible, but the love and support of my family have always been there. Power Up! and the LRS have taught me to value and respect myself. Now, because I love and value myself, people recognise and appreciate me and my work”.

Nozi shared salt and pepper containers from her mother-in-law: “Her support meant the world to me… This is my first Women’s Day filled with joy and no fear…But even if others don’t see me, I value myself, and my journey has made me strong”.

Manini shared a scarf from her mother and a necklace from her grandmother: “My mother taught me how to crochet and cook. My cooking skills have become exceptional, and my school team even notices when I am absent.”

Babalwa recounted her experience with her contract expiring, saying, “I felt down when my contract expired, but my grandmother’s encouragement kept me motivated…No one appreciated the invisible work I did, but it made me visible”.

Sonto said “Gogo taught me many things, including how to love people. When I arrived at PowerUp! I discovered that the love she taught was the same love that exists in this space. That is why I adore you all”.

Ntombana shared that she carries her grandmother’s strength with her, adding, “When my grandfather came home from the city, she would ask us to serve him milk with this special jar”.

Exploring identity: What does it mean to be a woman and a worker?

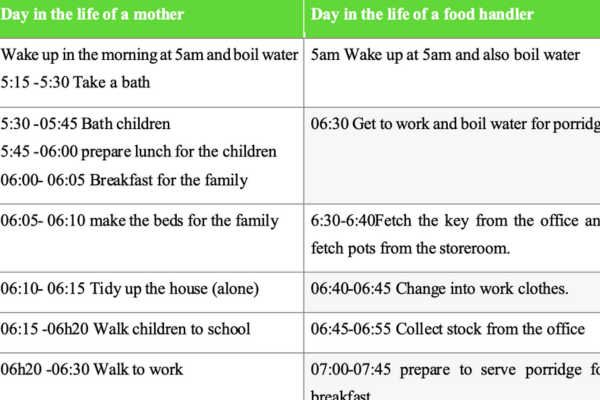

A mapping exercise revealed the food handlers’ dual roles as mothers and workers in the NSNP. Their days start before dawn with tasks at home, which mirror those at school.

Food handlers are visible in their duties but their value is unseen at home and in the workplace. One food handler noted, “We are seen but we are invisible”. This is compounded by the expectation that they should be the primary caregivers. Their maternal instincts extend to the children at school, but while this is fulfilling, it also leads to exploitation.

As one food handler explained, “The children call us ‘moms’ at school, which makes me proud”. However, this role often leads to them being called upon to comfort distressed children, even when they have meals to serve, as one food handler reported, “I spent thirty minutes in a Grade R class comforting a child who missed her mother. Every time the child cried, the teacher would come to get me from the kitchen”. This nurturing is often taken for granted, seen as an extension of their identity rather than work that deserves recognition and pay.

Similarities

Food handlers at home and work engage in nurturing activities by preparing food, ensuring others are fed, and providing emotional support, often acting as mother figures to children at school.

Their daily routines involve similar tasks such as meal preparation, cleaning, and child care. Much of their work is unpaid and unrecognised, often deemed “women’s work,” which diminishes its perceived value at home and in their jobs, leading to underpayment.

The skills required in both settings, like cooking and cleaning, are transferable, but their value differs. Both roles demand significant time commitment, with food handlers often working long hours and remaining on call for domestic duties.

Differences

The major contrast lies in how their labour is valued; while domestic work is unrecognised and unpaid, their work as food handlers is essential yet also undervalued. Their home duties are private and invisible, while their professional roles are public but still lack recognition.

Societal expectations compel women to nurture, both at home and in their jobs, while men are not held to the same standard. Although food handlers are part of a formal workforce, they often lack the recognition associated with their roles, which are viewed as extensions of their domestic duties. Male counterparts in similar public roles typically receive better compensation and acknowledgement.

The impact of undervaluing

The food handlers face many challenges, including being underpaid, overworked, and not receiving payment for leave. When they take time off, they must pay for their substitutes from their already meagre stipends. They also have inconsistent pay dates. The school administration and staff do not fully respect their work, expecting them to “act like superwomen”. This is despite the fact that they are indispensable to the smooth running of the NSNP. The blurring of their roles as mothers and workers leads to a situation where they are always on call, with no work-life balance.

"The school expects us to act like superwomen, ensuring that children eat every day, even when we are sick. We must make the same 'plan' we make at home to receive praise and recognition once a year from our children and spouses."

Vonteer Food Handler

Men’s work, whether in the kitchen or elsewhere, is deemed productive and valuable, whereas women’s work is often unrecognised and unpaid.

“We grew up seeing our grandmothers grow food for the entire family, yet their labour was never regarded as work. When men do it, for example, as gardeners in domestic work, it suddenly becomes valuable and paid."

Vonteer Food Handler

Volunteer Food Handlers advocate for the inclusion of school gardening in the curriculum to help learners value food production, take responsibility for their nutrition, and support community-led food sovereignty.

The food handlers seek recognition for their essential roles at home and in the workplace. They want their labour to be valued, whether they are nurturing their families or contributing to improved school attendance and learning outcomes through the NSNP. Their struggle is not just for themselves but for all women whose contribution is undervalued, underinvested in, unseen, and taken for granted.