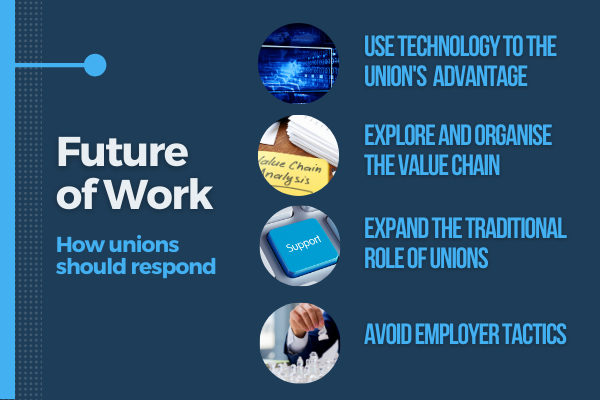

Explore and organise the value chain

The first is the need for trade unions to revisit the way in which they organise through acknowledging the broader value chains in which they operate. Although the focus of a union is the workplace, broader value chains and the dissemination of power are starting to play a more prominent role. Knowing where and how a company is situated in a value chain can help the trade union understand how to best negotiate for better pay or conditions of work. Revisiting strategies will have to be done on a step-by-step basis, but will start, for example, through a retail worker looking beyond their own workplace at something such as distribution centres that influence the functioning of the company as a whole.

Use technology to your advantage

Expand the traditional role of unions

The third relates to the expansion of the traditional role of unions. Traditionally trade unions focus on issues such as wage increases, benefits and working conditions during negotiations. Going forward, automation in the workplace will require an increased focus on issues relating to “education, training, and legal support in an increasingly complex environment” (Hodgson, 2016: 213). If the fourth industrial revolution is to result in a positive effect on employment, the reskilling of the workforce is pivotal.

Avoid employer tactics

- Guaranteed minimum working hours

- Job guarantees for the length of the CBA

- Restrictions on staff dismissals

- Restrictions on sub-contracting

- Protection of non-permanent workers

- Education and training (including re-skilling to meet new skills demands)

- Arntz, M., Gregory, T. and Zierahn, U. 2016. “The Risk of Automation for Jobs in OECD Countries: A Comparative Analysis”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 189, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jlz9h56dvq7-en

- Hodgson, G. M. 2016. The Future of Work in the Twenty-First Century. JOURNAL OF ECONOMIC ISSUES. Vol. L No. 1 March 2016. DOI 10.1080/00213624.2016.1148469

- Wright, M. J. 2018. The Changing Nature of Work. AJPH SPECIAL SECTION: WORK. March 2018, Vol 108, No. 3)