South Africans wish to see men and boys change their violent behaviour towards women and girls to stem the worsening tide of male violence against females in the country.

There have been numerous interventions – policies, programmes, campaigns – by government, civil society and the private sector to address this scourge. But, these efforts are failing as the problem is getting worse.

In June 2020, President Cyril Ramaphosa declared male violence against women a second pandemic in South Africa, adding that one woman is killed every three hours in the country. The country has one of the highest rates of rape in the world, with 132.4 incidents per 100,000 people.

Also in 2020, the government’s Gender Based Violence Command Centre, a call centre to support victims of gender-based violence (GBV), recorded more than 120,000 victims in the first three weeks of the lockdown.

The reason for the failure of the various interventions is because they are not addressing its psycho-social causes. My research on the subject shows that to change male violent behaviour towards females, there is a need to focus on changing male thought patterns that drive gender-based violence and femicide.

Controlling or reducing violent behaviour requires uncovering the linkage between people’s perception of situations and their behaviour.

I am a gender and development expert and have consulted for the United Nations Population Fund and the KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Government since 2011. I recently contributed to the province’s gender strategy plan 2020-2024. The yet to be published plan outlines, among other things, the need for the change of behaviour by boys and men towards girls and women as a way of promoting safety for girls and women in the province.

Across the country, the problem of gender-based violence and femicide is structural and fuelled by inequalities that transect race, class, gender, sexuality and age. It is prevalent throughout the life-cycle stages for women – from infancy, girlhood, adolescence and adulthood. The economic costs for the country have been huge.

What research says

Several studies have sought to explain the causes of gender-based violence in South Africa. Many of these fall under four broad categories; socio-cultural, economic, legal and political.

Socio-cultural: For example, patriarchy and the gender inequality it produces have been implicated as the root cause of violence against women. Studies show that rape is mainly caused by ideas of masculinity that fuel male sexual entitlement to female bodies. Others highlight how particular understandings of masculinity legitimate unequal and often violent relationships with women.

Economic: Poverty and unemployment are disproportionately borne by females, and makes them vulnerable and susceptible to abuse by male providers.

Legal: There is a difference between the public and private spaces which gender equality legislation and policies do not cover. For example, the Domestic Violence Act in itself has not deterred male violence against women which occurs in the informal and personal spaces of gender relations.

Political: Although there is political will to make gender equality legislation and policies, there is little or no will especially at lower levels of government to implement them. For instance, political leaders themselves perpetrate gender-based violence, sometimes with support from their parties.

An important point to note though is that no single factor can explain this violence in South Africa – or any society for that matter. A myriad of factors contribute, and their interplay lies at the root of the scourge.

The gaps

As the literature overview on the causes of gender-based violence in South Africa shows, little or no attention has been paid to its psycho-social causes – the interrelation of social factors and individual thought and behaviour. In this case, they are the thought patterns that inform how men and boys see women and girls, and how these perceptions in turn inform violent masculine behaviours towards women and girls. Neglecting this has implications for addressing the problem.

This gap in literature is also reflected in the responses by government, activists and civil society, which have failed to arrest the scourge in spite of the efforts and resources put into it since democracy in 1994.

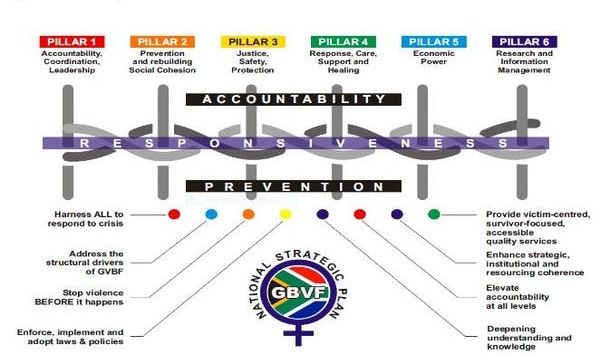

Government’s latest policy response, the GBVF National Strategic Plan 2020–2030, which has significant activist and civil society inputs, reflects this gap. Its six pillars focus on leadership accountability, prevention, enforcing justice, victim support, economic empowerment and research. These are useful priorities. But, none of the plan’s six pillars and their intended outcomes reflect any psycho-social priority.

Figure 1: The six pillars of the NSP 2020 - 2030

Source: Presidency, South Africa

Why what men think of women matters

As I have argued in my research, people are the product of their cultural environments, which define their behaviour.

In other words, our cultural learning largely determines what we are consciously aware of, and how we conceptually structure that awareness into behaviour.

Findings from focus group discussions with working class men (35 years average age) in Umhlathuze Municipality (KwaZulu-Natal) and university students (20 years average age) at the University of Zululand and the University of KwaZulu-Natal, show how these thoughts influence dangerous masculine behaviour.

According to one of the older men:

I see women (and my wife) as public enemy number one who must be curtailed always.

The younger men expressed similar views of women. According to them:

women are mentally strong while men are only physically strong, so when we cannot cope with their mentality, we beat them.

Combating violence against women

Given the link between perception and behaviour, it is understandable how oppositional and stereotypical perceptions men hold of women can foster violent masculinist behaviour. For instance, seeing females as “properties” can produce an entitlement mentality among males. This makes it difficult for them to let females live in peace when they end romantic or marital relationships.

It is the feeling of “ownership” that give males the audacity to want to keep controlling and brutalising females they are no longer involved with. Therefore, to change and possibly eradicate male violence against women in South Africa, intervention efforts must be targeted at changing how males see females.

When males are socialised to start seeing female as humans with rights too, just as they were perceived in pre-colonial times, they will start treating women with the decency, due regard and respect that they deserve.

Changing perceptions cannot be legislated. This perhaps explains why a legalistic or policy approach alone is not cutting it. Changing perceptions to change behaviour, which usually occurs at the private and personal levels of gender relations, will require specific interventions aimed at re-socialising boys and men.

Some of these include changing the curriculum from primary school to tertiary education to place women alongside men in history and social studies. Co-parenting from birth to break the backbone of patriarchy is another possible long term strategy in this regard. These are doable and can be implemented alongside other interventions to combat male violence against females in South Africa.![]()

Christopher Isike is Professor of African Politics and International Relations at the University of Pretoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.