For the past three years in my capacity as an LRS staff member, I have been a facilitator in a pilot social action project at the Meadowlands Clinic in Soweto in South Africa. The project brought together the different actors involved in the health system, including all the providers and beneficiaries, at a local level and in one locality, to take up actions that will collectively impact on reducing the high levels of gender-based violence in the Meadowlands Clinic.

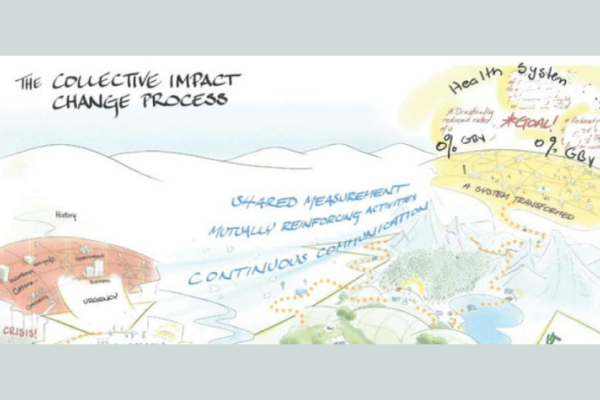

Together with a co-facilitator, we supported a core group of worker- and community leaders’ work with a collective impact and emergent learning approach to experiment with actions for reducing the levels of gender-based violence in the clinic. The core group was encouraged to then share what they are learning across organisations they are part of: in the union, through clinic and district health forums and community organisations and structures. The aim is to influence what’s taking place in the health system more generally.

Over this period we have seen a decrease in the levels of violence in the clinic. More recently, however, the core group in Meadowlands report feeling increasingly frustrated at their attempts to sustain the initiative in a context of deteriorating facility infrastructure and working conditions.

In the monthly forums between the LRS facilitator and Meadowlands Core Group, numerous challenges in the health system have been discussed, including lack of staff, equipment and maintained infrastructure; operational managers are expected to fight for resources; low staff morale and the absence of effective communication channels between the staff and Department of Health management; Extended Public Works Programme (EPWP) workers brought in as a source of cheap labour and taking on some of the core functions in the clinic and the Department of Health encourage patients to exercise their rights but not their responsibilities in relation to their health and the staff at the facilities.

For this article, I will focus on two key infrastructure challenges: the lack of effective sanitation facilities; and the working conditions of community health care workers who form part of the Ward Based Primary Health Outreach Teams (WBPHOT’s). WBPHOT’s form an essential component of the primary health care provision promised by the government.

While health institutions are public places there is almost an unconscious entering of the private space when the patient or worker uses the toilet or when the health care worker working in the community enters the home of a patient. Within the gendered sphere of health care as devalued reproductive work, we are seeing a further devaluing of conditions and work associated with some of the more intimate aspects of the patient and staff’s conditions in the health system, that is, the individual use of sanitation facilities and the health care work provided in the home of the patient.

There is a gendered separation of social reproduction from economic production with women largely responsible for social reproduction. In this context care work as social reproductive labour is considered to be part of a woman’s natural role in society and is mostly not recognised as work. So, when care work does take place within the public, it continues to struggle to be recognised and valued.

In our monthly forums, the Meadowlands Core Group members have started exploring the intimate experience of the patient and staff member who is forced to use the toilets of the public health facility. For the Core Group a key approach to addressing gender-based violence (GBV) in the health system is about restoring the dignity patients and staff will experience with proper sanitation facilities, as well as the dignity care workers will experience when their work is recognised as being essential to the functioning of the health system and their conditions and remuneration reflect their status as employed health care workers.

Sanitation and dignity

Every time we use a clean and functional toilet we are exercising a basic human right to dignity – the dignity of the person using the toilet but also the dignity of the worker who is cleaning the toilet.

Patients attending the health facility and staff working in the facility are away from home and forced to use the toilets in the health facility. Even though sanitation is a cornerstone of public health, patients and staff speak about unhygienic conditions; a lack of sufficient toilets; an absence of toilets for patients or staff with special needs and the absence of maintenance.

A 2016 Public Health Facilities audit by the Office of Health Standards Compliance (OHSC) results identifies the lack of cleanliness as a challenge in clinics in all of the nine provinces of South Africa. While no specific mention is made of toilets, one can infer from the survey that the lack of proper sanitation is a key feature in what is being described as the lack of cleanliness.

Inadequate and unhygienic sanitation services affect the clinic population differently. Elderly chronic patients at times soil themselves if there are not sufficient toilets catering for their special needs. With unhygienic conditions, women and girls face the possibility of reproductive tract infections. During menstruation and pregnancy, it’s even more critical that women have adequate sanitation facilities.

Where the toilets are situated, the lighting used and the proximity of security guards, are all factors that play a role in whether women and children feel safe using the toilets in the clinic.

Keeping the toilets clean also falls largely in the hands of the female cleaning staff at clinics. The lack of proper protective clothing, equipment and the appropriate chemicals, puts them at huge risk of falling ill. All of this is happening in the clinic, the very health institution that is responsible for supporting wellness and raising awareness about healthy living.

Union representatives, Clinic and District Health Committee Members, Ward Counsellors, representatives from community structures all form part of the Meadowlands Core Group. All of the actors in the group are committed and passionate about restoring dignity to the staff and patients working and attending the clinic. Focusing on improving the toilet facilities is one example of different actors working together to address a challenge that affects everyone.

The union representatives are committed to addressing the occupational health and safety issues facing the cleaners as well as the inadequate conditions of work ( the lack of adequate toilets facing health care workers and support staff in the clinic). The Clinic Health Committee representatives are committed to highlighting the different needs of all of the clinic population.

Representatives from the community organisations and ward committee together with the Clinic Health Committee are committed to encouraging patient responsibility in maintaining the toilets clean and preventing vandalism. The Clinic Health Committee also acts as the “eyes” and “ears” of the community in following up on existing and planned interventions at the clinic.

The intention is to bring on board the clinic management as part of the ongoing lobbying for improved maintenance and resource allocation, for example, building of toilets for people living with disabilities; increasing the numbers of toilets taking into account the specifics needs of the women, men and gender non-conforming people who attend the clinic, proper signage indicating where the toilets are situated; ensuring that materials like soap and paper towels are regularly available and employing sufficient staff to maintain the toilets. Communication with the Department of Health remains a challenge for the core group.

Inadequate sanitation facilities is one example where the voices of women, people living with disabilities and the elderly are ignored. Through the gender sensitisation discussions in our monthly forums, the trade union and Clinic Health Committee are encouraging all voices to be heard at the facility level through the management committee, the district and provincial bargaining forums and the District Health Committee.

In the group, there is a growing awareness of how the concerns and needs of women or the elderly are very seldom taken into account in the provision and design of sanitation facilities. One example in the Meadowlands Clinic Context is the ramp for wheelchairs which clinic staff describe as completely “wheelchair unfriendly”.

Dignity for members of the Ward Based Primary Healthcare Outreach Teams

The Ward Based Primary Healthcare Outreach Teams (WBPHOTS) are the first national attempt to formally integrate community health and care workers into the public primary health system. With the primary health care system, there is a focus on addressing what the World Health Organisation, defines as the social determinants of health. Social determinants are the conditions in which people are born, live, grow, work and age.

There is an expectation on the part of the Department of Health that while professional nurses with their clinical training are largely responsible for the curative aspect of health care, the WBPHOTS will have the range of skills, competencies and attributes to provide community and home-based interventions, care and support.

WBPHOTS might have a similar ring to the word Robots, the robots that ostensibly will be taking over the workplace with the 4th Industrial Revolution and promising a move away from manual labour, yet the working conditions facing community health care workers resemble more that of the Victorian era than some futuristic society.

Public Health and Social Development Sectoral Bargaining Council (PHSDSBC) Resolution 1 of 2018 on the standardization of remuneration for community health workers in the department states that a community health worker who forms part of a National Department of Health database will receive a non-service remuneration payment of R3500.

A google and dictionary search did not provide any definition of the term “non-service” so the conclusion one can draw is that nonservice remuneration is actually a stipend of R3500.

The use of the term “non-service” instead of stipend seems disingenuous creating the impression that the payment is something more than a stipend. While a stipend is an acknowledgement and form of compensation for the work performed, the community health care worker isn’t considered an employee with the rights and benefits afforded to employees under South African labour law.

If the WBPHOT is seen as an essential part of the primary health care system, why is it that the role of community health worker has shifted just slightly above volunteer? Is it because the work being performed is seen as “women’s work”, the reproductive role that is supposed to come naturally to women and is therefore not real work, not salaried work?

The PHSDSBC Resolution speaks of ensuring appropriate implementation and management of occupational health and safety processes for all members of WBPHOTS. The workplace for the Community Health Care Worker is primarily the home. The community health care worker travels from home to the clinic and then walks to her (the majority of healthcare workers are women) primary place of work i.e. the homes of her patients. She is most likely to be walking alone and will carry out her work alone. She is not provided with a cellphone or airtime to raise any kind of alarm if she is in danger. Inside the home, she is expected to assist patients with essential services like bathing patients without any support or equipment for lifting or supporting the patient exposing her to overexertion, possibilities of tripping and falling and musculoskeletal injuries. Without sufficient and proper protective clothing and gloves, she runs the risk of exposure to infectious diseases. In the work of cleaning and disinfecting the work areas, there is the possibility of exposure to harmful chemicals if the Department of Health hasn’t provided her with the appropriate cleaning and disinfecting chemicals.

An ever-present risk in the homes she visits is the threat of violence from the patient, the family members and neighbours. There is also the question of sanitation, or toilet facilities for the community healthcare worker. What provision is made for her to relieve herself or does she have to wait until she returns to the clinic after the home visits? So when the resolution speaks about occupational health and safety measures, it’s important that the voices of the health care workers are heard and that the specific challenges of their work and workplace are understood and appreciated.

Back at the clinic, the community health care work has no real workspace. In an Albertina Sisulu Executive Leadership in Health Program 2015 publication, Rapid Appraisal of Ward Based Outreach Teams, an appraisal of teams in selected districts and sub-districts countrywide identified physical space and a general shortage of essential office equipment, stationery and access to phones as the challenges in functioning effectively.

WBPHOTS are located in clinics but aren’t made to feel part of the clinic. They have no dedicated physical space, or place to keep their work materials and are generally left feeling like they are “imposing and adding further to the over-burdened clinic staff workload”, according to the Rapid Appraisal of Ward Based Outreach Teams publication.

There’s also the challenge of team leadership. The PHSDSBC Resolution identifies the professional nurse as being accountable for the oversight of community healthcare workers. The resolution makes provision for the professional nurse to be supported by trained enrolled nurses.

There is a dire shortage of trained nurses in our health facilities, making it difficult for the existing clinic staff to fulfill the expected leadership roles, and leaving teams rudderless. The absence of team leaders or the reluctance on the part of professional nurses to take on the leadership roles further exacerbates the community healthcare workers sense of isolation.

Community Health Care Workers are treated like the housewives of the health system, expected to serve with a smile and with no consideration for their own safety and wellbeing while denied the status of a worker and a salary. They don’t have the support and the required tools. What they do is not seen as work, where they work is not seen as a workplace and what they say is not heard.

In our monthly forums in the Meadowlands Clinic, we have observed the members of the WBPHO team leave in the morning and return in the afternoon, quietly going about their business, visible but silent. All of the role players in the Core Group have committed themselves to break this silence.

Conclusion

Strengthening social dialogue for collective impact

Over the past three years, the Meadowlands Core group has focused on creating safe spaces to encourage dialogue between the different role players in the clinic and community. This has led to a wide range of actions from different role players committed to reducing the levels of gender-based violence in the clinic. The LRS has supported the Core Group in creating these safe spaces and this has been important in role modelling ways of engaging and working collectively.

Historically the Clinic Health Committee and Trade Union have worked in isolation or competed with each other. With their common commitment and passion for restoring dignity for patients and workers, they are exploring ways of having a more collective impact where they are officially represented.

Clinic Health Committee and Trade Union are using their different spaces of engagement and bargaining to have their voices heard and are exploring joint engagement with the Department of Health MEC at a District Level.

Presently the union engages with clinic managers at a sub-district level and the Department of Health at a provincial bargaining council level. The union is now exploring the possibility of labour and the community representatives both meeting at the district level with the Department of Health to place the restoring of the dignity of patients and workers at the heart of future collaboration.

This article is extracted from the 2019 edition LRS Bargaining Indicators.