Workers join these organisations so that the organisations can raise the workers’ issues and protect them from exploitation. Without a strong collective bargaining function, organisations won’t be able to meet their goals of representing workers.

The process of negotiations forms the central part of collective bargaining. A union enters negotiations with an employer in the hope of winning a collective agreement that favours its members. The two parties negotiate until they find a compromise that they both agree on. Behind the talking, there is a power struggle. The workers put whatever pressure they can on management to agree to their demands, and management uses its tactics to try and get the workers to agree to their offer. Sometimes there is an agreement, sometimes there is not. When no agreement is reached, it is called a dispute and the parties involved can then call on a third party to mediate or arbitrate.

Bargaining levels

1) Plant or company level bargaining

Collective bargaining may take place at the plant level, involving one or more workplaces that are part of a larger enterprise.

Bargaining may also take place at company level and may cover more than one workplace. Either way, bargaining can involve one or more trade unions or worker organisations, but only one employer.

2) Centralised sector-level bargaining (bargaining councils)

Section 27 of the Labour Relations Act No 66 of 1995 states that one or more trade union and one or more registered employers’ organisation may form a bargaining council in a sector. Some bargaining councils are national, while others are regional.

The purpose of the bargaining council is to regulate (control) wages and conditions of employment in a sector. Agreements reached in these negotiations are called settlements and can be extended by the Minister of Labour to non-parties (workers and employers not registered with the council).

3) Administered wages and conditions at sector level (Sectoral determinations)

This level regulates wages and conditions of employment for vulnerable workers in sectors where they are likely to be exploited or where workers’ organisations or trade unions are absent. 1 These sectors include farm workers, domestic workers, the wholesale and retail trade, the hospitality sector, and the taxi industry. A commission established in law conducts research and convenes public hearings in order to collect proposals from workers and employers. This commission then makes recommendations to the Minister of Labour. Once the Minister approves the recommendations, a sectoral determination containing wage rates and conditions of employment is published and applies to all employers and all workers in the sector. Since 2019, this function falls under the National Minimum Wage Act.

4) Informal economy forums

In this instance, the sector itself is informalised (for example street traders and waste reclaimers) or the employment relationship is informalised (for example, community health workers).

Often, many of the conditions that exist for bargaining in the more formal workplace do not yet exist in more informal settings. The direct employment relationship does not always exist and the bargaining partner is yet to be established. There is no recognition of the worker representatives by employers or those who regulate their workplace. The bargaining unit is not defined. Bargaining levels may range from very localised levels to bargaining with municipalities and with national government.

Usually, your negotiating counterpart is responsible for implementing the agreement. Still, members and the organisation may have responsibilities too – sometimes agreements are not implemented, or only partially so. Other times agreements are manipulated or deliberately misinterpreted.

In the informal economy many of the agreements are with government and public authorities. This creates an unstable situation as they are often disregarded or changed when new parties, people and policies come in.

What can we do?

- The agreement should be very tightly worded and signed by the highest authority, plus those responsible for its implementation.

- Ensure that the agreement binds future political parties, policymakers and bureaucrats.

- Insist that the agreement is made known widely throughout the public authority. Ask for proof that this has been done.

- Work towards formalising the negotiating forum so that it is recognised and respected.

- Carry out your side of the bargain! Don’t give the other side a chance to say that you have broken the agreement!

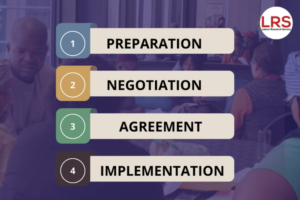

The four phases of collective bargaining

No matter in which sector you work, or in which part of the economy, there will be some aspects of the four stages of bargaining that can be translated into your experience. Every negotiation, whether in the informal or formal sector, in a small organisation or a multinational corporation, will go through these stages to a greater or lesser degree.

The four phases of collective bargaining:

1. PREPARATION

Preparing for bargaining is key to success, and a vital part of the collective bargaining process. The difference between being reactive and proactive is preparation. The advantage of preparation is that you can manage the problems and challenges that arise better. You will already have the information you need at hand and have thought through various solutions as a team. This is a substantial phase of the collective bargaining process – be warned: it takes a lot of time and energy.

A checklist for preparing for bargaining

Put together the bargaining team

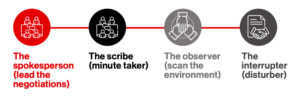

A bargaining team is elected at the outset of the bargaining process and roles can be assigned to each member of the negotiating team. There are a number of possible roles, including:

The spokesperson will lead the negotiations. They will do the opening and the closing of the negotiations. Strong leadership is important in this role for ensuring compliance and productivity. It is also very important that the spokesperson on each side has the backing of their constituents, and is a representative of the group. This means that an elected leader in a union that is representative of a certain type of worker holds a stronger position in negotiations than someone who does not have this kind of backing.

The scribe will take the minutes for the team.

The observer will read the body language of management, analyse the atmosphere at the bargaining table and call for a caucus when need be.

The interrupter will be the person that steps in to confuse management by saying things that are not relevant to the negotiations. Develop signals to be used by your team when communicating to each other in front of management.

Another member of the union negotiation team can be elected to take accurate notes and keep a record of all decisions and agreements made in the negotiation. You may need this if management later tries to deny that a certain agreement was made.

The union should also plan who will present the argument and motivation for which demand. It is best for as many shop stewards as possible to get direct experience with negotiating. However, the organiser should always be there to give support to the arguments put forward by the shop stewards. Make sure the bargaining team is representative of the workers, especially taking gender representation into account. Don’t accept ‘No’ from a bargaining partner that does not have the authority to say ‘Yes’.

Gather information and conduct research

It is important that organisations have a clear vision and objective for collective bargaining. Preparation is a key to successful negotiations and as a negotiator you are required to gather information that will help you understand the members you represent and assist you in representing your collective interests.

Information gathering: what information can I get myself?

This process of gathering information starts with understanding ourselves. Much of what we do in the workplace and in our organisations or groups is informed by the power we hold – and key to this power is our gender identity and roles. Think about the following.

- What linkages can we see between our gender, our position and what we do?

- Is it something you are involved in any way? How are you involved?

- Is bargaining something that happens over there, something that is done by other people? Who are those people?

- Is what gets onto the bargaining agenda shaped in any way by gender and power relations in the workplace and in the union?

- Is what stays on the bargaining table shaped in any way by gender and power relations in the workplace and in the union?

Information gathering: What information do I need from others?

Organisations should put mechanisms in place to manage information (like collective agreements, membership, reports and other issues that relate to collective bargaining). This assists the organisations to assess their performance and be able to implement new strategies when facing challenges. It is the duty of the organisation to assess and develop the skills of the workers that could be trained as negotiators.

Research questions

- What facts and figures can help you motivate your demands?

- What experiences can you quote that will support your case?

- Are there laws, regulations, agreements or precedents that might assist?

- What other factors in the environment might affect your case?

- What are the likely reactions of your negotiating counterpart?

- Where is your opponent weak and where are they strong?

- Where are you weak and where are you strong?

- Where are your opponent’s decisions taken?

- Who are your potential allies and supporters?

Convene a general meeting – the process of collecting demands

When you have all the information, (information that you would like to test with the workers) the next step is to convene a general meeting to hear and collect demands from workers. The purpose of this general meeting is to assist in analysing and quantifying workers’ demands using the information collected to build your case. The demands may then be forwarded to the company or management in writing together with the proposed date and time for the meeting.

Facilitate approaches that allow all workers to be heard.

At plant level, each shop steward represents a different department or group of workers. Before negotiations can begin it is necessary to put together the demands of all workers from the different departments into one set of common demands. At plant level, coordination can take place in shop steward committee meetings. Some demands should be coordinated with the advice of an organiser.

At company level, it is very important that the demands of all the different factories are taken into account. Often one factory is in a weaker position than others, and this problem should be corrected in the company negotiations. At company level, coordination should take place through a company shop steward and council meeting, where all shop stewards from the different factories meet to discuss their problems and formulate their demands and plan their strategy.

At national bargaining council level, there are many differences among the different factories and workplaces represented. Some are small and some are big; some are weak and some are well organised; some are in major industrial areas and some are located in rural areas. These differences have to be considered when a final common set of demands is put together for negotiations. Coordination of national negotiations can be done through national meetings where shop stewards from different regions and companies put forward their region’s proposals and develop a national set of demands.

Prepare members, allies and the public

Make sure members know when negotiations will take place and when and how they will get a report. Keep them interested and excited. Part of your strategy could include a supportive demonstration by members and/or regular negotiation bulletins.

Inform other workers’ organisations and potential allies about the negotiations. Set up channels for technical support.

Highlight the issues within the community and, where appropriate, to the public at large.

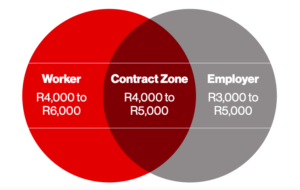

Determine your positions

Before going into negotiations, the negotiating team must determine these parameters: what is the ideal settlement, what is a reasonably expected outcome (or reasonable settlement), and what is the least you will be happy with (fall-back position). This provides your team with a framework for negotiations. It is not for sharing with your bargaining partner.

The fall-back position is the least favourable outcome – beyond this outcome, some form of conflict would be preferred (e.g. a strike). This position represents the last resort of the parties involved. In Ralph Johnson’s book, Negotiation Basics: Concepts, Skills and Exercises, this is referred as the ‘worst acceptable deal’. Fall-back positions are made on instructions from constituents and also on principles of fairness.

One of the most important pre-conditions to successful negotiations is the existence of a contract zone. This means that some kind of middle ground, or common ground, exists where both parties are satisfied with the outcome. This is the space where the negotiating parties’ interests overlap. If there were no difference in interests, there would be no point in bargaining:

An example

If the employer wants to pay the workers R5,000 per month, and the workers want R5,000 per month, there is no point in bargaining.

However, if the workers will accept a range between R4,000 (fall-back position) per month and R6,000 (ideal settlement) per month, and the employer wants to pay between R3,000 (ideal settlement) and R5,000 (fall-back position) per month, there is an overlap. This overlap is what is called the ‘contract zone’. So, in this example, we know the contract zone is between R4,000 and R5,000 per month. In order for negotiations to begin, both parties must believe that a solution exists.

Establish your priorities

When shop stewards meet to discuss which demands to put forward for negotiation, they have to consider which demands are the most important and urgent and which demands are less important and urgent. Once the prioritised demands are agreed upon, the union can unite, mobilise, and campaign around them. When workers choose which demands to put forward and what they are going to fight for, they need to consider their organised strength. It would be no use putting forward a long list of strong demands around major issues if the union is very weak. On the other hand, if the union has a lot of active worker support and there is a militant mood, then it would be a waste for the union just to put forward small demands.

In addition to a set of common demands, workers from a particular company or workplace might have a certain problem that needs to be brought into negotiations, and these specific demands must then be added to the common demands.

Clarify your mandates

According to the tradition of democratic worker control that we have built into our trade unions, elected worker leaders and union officials must represent the interests of the worker members. Every union will have its own structures for making sure that whatever the representative takes into a meeting with employers comes directly from workers, and that whatever is discussed in meetings with employers gets taken back to workers.

For negotiations, a shop steward represents a constituency of workers. What that constituency is depends on the level of negotiations. In preparation for negotiations, shop stewards will collect demands from workers. Once a single list of common demands has been drawn up in shop stewards’ meetings, the shop stewards should take these back to workers to make sure that this set of common demands has their support. The union cannot expect to win demands that do not have the support of workers.

Agree to timing

The timing of negotiations is very important. While it is difficult to determine the ‘perfect’ timing, forcing issues too early may weaken the party’s negotiating position. The best time to bring up issues is when parties are more equal: when neither party is able to solve the conflict on its own, and each party is necessary to create a solution.

An example of this is when an employer (e.g. a retailer) can’t keep its doors open without workers, and that the workers won’t have an income without the employer. This means that both parties need the other to come to a solution. Each party holds some of the cards, but no party has the upper hand.

A good tactic here is to make sure the other party (the employer) understands that the situation will only get worse if negotiations don’t move forward.

Set-up a pre-bargaining meeting

Before you begin negotiating you must decide on the topics that you want to explore with the other party at the negotiation table. For example, early settlement, opening offer issues to be negotiated, ground rules, venue, and size of the negotiating teams.

A pre-bargaining meeting is needed to decide on the above-mentioned information. Identifying potential difficulties before the negotiation begins can help boost your confidence, and knowing when to introduce or avoid these difficulties can provide a useful tactical advantage.

Set the agenda

Negotiators should be aware ahead of time what issues will be discussed during the negotiations so that they can prepare. Should an issue come up that was not on the agenda, the negotiations may be undermined. It is very important to determine the agenda ahead of time: list and define the issues which are important to both partie. List demands in order of priority, as it will help all parties to remain focused during the negotiations.

Share the issues to be negotiated among the team members. This is very important as it allows you and your team to be on the same page, preventing a team member from diverting from the objective or goals.

Agree to timeframes

Time is very important in most bargaining exchanges. There are lots of arguments for and against imposing timeframes for negotiations, but the prevailing argument is that timelines and deadlines are necessary in order to ‘push’ bargainers to agreements and to create a sense of urgency. Giving an endless amount of time might lead to bargainers using ‘delaying tactics’.

Choose a venue

The choice of venue for the negotiations has an effect on the psychological climate of the negotiations. If the negotiations are held on one party’s territory, that party has power over the physical arrangements, which in turn affects all the parties attending. This gives the host party an advantage, much like ‘home ground advantage’ in sport. Guests to the site may view themselves as inferior and this might affect their behaviour. A neutral site is often more appropriate.

Agree to the rules

It’s really important to have a set of rules for the negotiations. Rules provide stability during what can be seen as an unstable situation.

As part of the rules, it is important to determine how the decisions would be agreed upon during the negotiations. The parties present must accept the decisions made as being binding once an agreement has been reached. This could be by means of numerical majority, in a system of voting. Regardless, these details need to be clearly stated in the rules.

Checklist for preparing for negotiations

1. Revisit demands: Before you enter the negotiations or bargaining table, always make sure that you have gone over and are familiar with your demands, management offers, trade-offs, your alternatives for each demand/offer. Check in with your team to ensure they are ready for negotiations. to start.

2. Update and consult members: A consultation process with members can also be initiated to update them regarding the outcome of the pre-bargaining meeting. This helps members to feel involved in the whole process and own it. As a negotiator, you enter the negotiations on their behalf, meaning it is their mandate that counts, not yours. During preparation, a negotiator must get to know and understand their constituency (for example, their workplace, age, gender and challenges).

The negotiator must also be able to forecast the outcome of the negotiation as this will assist in preparing for a dispute if it arises. Make sure members know when the negotiations will be taking place and when and how they will get a report about the outcome.

3. Strategise: Formulate a strategy (a plan to achieve your goals or objectives) and tactics (the methods employed to achieve a strategy) for all stages of the negotiations to assist in marshalling your arguments.

4. Determine the structure of negotiations: The structural components of negotiations are very important and greatly affect the behaviour of bargainers. The process involved in getting to know each other will consist of negotiators from both sides introducing themselves and their teams. State the objective of the meeting and put down the ground rules that will guide the proceedings.

2. NEGOTIATION

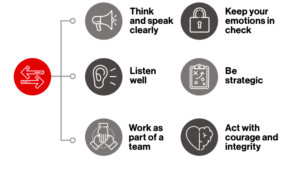

The second phase in the collective bargaining process is where you actually engage with the other party face-to-face, across the bargaining table, in order to negotiate the best possible outcomes for your members. Everything you’ve done in the first phase – all the hours of consultation and preparation – finally pays off. You have the information you need, you are well equipped, and so are your other team members.

This phase calls on another skill set – you are required to:

The process of negotiations

Each side will be given an opportunity to state and make arguments for their proposal (demands and offers). You need to state your case simply and clearly. Show the other party that you know what you are talking about and have confidence while stating your case. Your team members will motivate demands allocated to them to strengthen your case.

There will be agreements and disagreements. Stay calm and focus on the issues or offers put forward by management. Do not shy away from asking the opposite negotiating team for clarity or an explanation regarding their position, offer or response.

If you agree with some of the demands from the other party, get agreement ‘in principle’ to avoid confusion when there’s a dispute.

It is very important to keep an open mind when it comes to the kind of agreement you would like to reach. For example, the agreement must offer an acceptable solution to both parties and be inclusive (cover all workers in the workplace/sector, including workers in vulnerable sectors).

Caucus

If you feel that you are losing the arguments, or there’s disagreement in your team regarding some issues, stop the negotiations and request a caucus to allow you to think, get more information or to manage your emotions. This mechanism (caucus) will also allow you to touch base with your constituency regarding the progress of the negotiations.

Trust and good faith

Bargaining in good faith means that ‘once a negotiator makes an offer it cannot be retracted, and an agreement, once reached, is enforceable’.

Feedback to members

Always keep in mind that you represent workers and therefore keep them informed about progress in the bargaining table. Identify issues where there’s no agreement and request a fresh mandate from members. Make sure that members understand all the processes leading to the dispute mechanism if there’s no agreement reached.

After every round of negotiation, the negotiating team must report back to the workers who will be affected by the outcome of the negotiations. Plan carefully and collectively how you will report back to workers.

Using support materials such as pamphlets and charts, explain to workers what happened and why. Put forward options for workers to consider. Listen to all viewpoints, including those of women, and try not to allow one person or position to dominate. Try to reach consensus amongst workers – or at least consensus amongst the majority. If not, you may have to use a voting process.

3. AGREEMENT

Before the agreement is signed, make sure to read and understand every clause. Share the agreement with your constituency, leadership and/or legal department to check, amend or give input. File the agreement safely for future referencing. Review the negotiations with your team and address any challenges encountered at the bargaining table.

Reaching deadlock

If no agreement is reached, then negotiators must go back to the workers and discuss what to do. If there is no acceptable compromise that can be seen then the workers need to look at the possibility of declaring a dispute. It is also important not to delay taking a course of action lest workers lose interest and confidence.

4. IMPLEMENTATION

This is a crucial phase in the collective bargaining process. For an agreement to be considered legitimate, it should be successfully implemented. In this sense, the agreement itself is only the beginning of the process. Do follow up and make sure that what was agreed in the bargaining table is being implemented as per the collective agreement. Share the final agreement(s) with your members or constituency.

- Use it as an educational tool. What lessons have we learned? Give yourself time to reflect on the experience of negotiating.

- Use it to raise awareness of issues, about negotiations and about the organisation.

- Get workers to go out, spread the word and bring in new members.

- Provide publicity on the agreement. Celebrate the victory!

References

- Haroon Bhorat, Ravi Kanbur, Natasha Mayet, and University Of Cape Town. School Of Economics. Development Policy Research Unit. 2011. Minimum Wage Violation in South Africa. Cape Town: Development Policy Research Unit, University Of Cape Town.

- Johnson, Ralph A. 1993. Negotiation Basics : Concepts, Skills, and Exercises. Newbury Park: Sage Publications

- Atkinson, Gerald Gordon. 1977. The effective negotiator: a practical guide to the strategies and tactics of conflict bargaining. London: Quest

- Zartman, I. William, and Maureen R. Berman. 1982. The practical negotiator. New Haven: Yale University Press

- Harris, Peter, and Ben Reilly. 1998. Democracy and deep-rooted conflict: options for negotiators. Stockholm, Sweden: International IDEA

- Rubin, Jeffrey Z., and Bert R. Brown. 1975. The social psychology of bargaining and negotiation. New York: Academic Press

- Atkinson, Gerald Gordon, The effective negotiator

- De Silva, Sriyan. 1996. Collective bargaining negotiations. International Labour Organisation

Our bargaining processes | CEPPWAWU

Jerry Nkosi, Head of Collective Bargaining at the Chemical, Energy, Paper, Printing, Wood and Allied Workers’ Union (CEPPWAWU), speaks about the collective bargaining experience of the union and the lessons learned.