In many parts of the world, cooperatives are harnessing the “platform economy” for the benefit of communities as well as their members, and this movement is growing in strength. Could worker-owned co-ops in South Africa get a grip on the digital economy and, in doing so, contribute to help our communities stand together to win their socio-economic struggles? What does it take for a worker-owned co-op to survive economic challenges? Is it a quantum leap for a co-op to use open source software and transform itself into a platform co-op, taking account of the socio-economic context of South Africa? Is there any support for platform co-ops in South Africa? There are many questions and not yet many answers around platform co-ops in South Africa.

South Africa is a beautiful country and rich in mineral resources. It is also a country of shocking contrasts where millions battle the daily challenges of growing inequality and poverty. The official unemployment rate stands at a mind-blowing 34.4% (7.8 million people) in the second quarter of 2021, representing the highest rate since the global economic crisis of 2008, while South Africa remains one of the world’s most unequal societies with a Gini coefficient or wealth distribution index of 0.625.

The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified these problems. According to a recent National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS), 42% of adults in grant-receiving households lost their primary source of household income, while 54% of families are not receiving state support and are surviving on the brink of existence. A recent report by the International Labour Organisation identified job losses as the country’s biggest challenge, which became much worse during the COVID-19 lockdown period. Ordinary citizens, experts in labour law and other disciplines, and an array of civil society organisations as well as the government are looking for ways to navigate these deep-rooted social and economic challenges.

At this point, there are few indications of what is to be done fundamentally and structurally. But some short-term emergency measures have been taken. A necessary intervention is the rollout of an Unemployment Insurance Fund Coronavirus Covid-19 Relief Benefit to enable employers to pay workers during the lockdown. Only specific industry sectors and workers were considered essential in terms of disaster regulations. Besides delivering much-needed health services to the poor, priority rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine to the most vulnerable is beginning to happen. A further intervention to alleviate the dire economic situation of the broader population is the expansion of the social assistance programme for unemployed people to receive an unconditional monthly grant of R350 (or US$24) to improve food security. At present, this income support is only available until the end of March 2022.

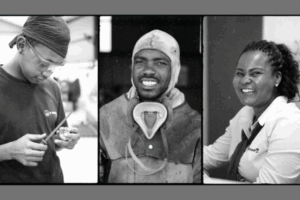

Creative and long-term interventions are needed to deal with the structural challenges faced in South Africa. In particular, there is the urgency to reimagine employment. Commercial digital platforms are fundamentally shifting how work is organised. But, according to the latest report (Fairwork South Africa Ratings 2020:Labour Standards in the Gig Economy) of the Fairwork Project, platform workers, “face unfair work conditions, and lack the benefits and protections afforded to employees” like the right to fair pay, fair conditions, fair contracts, fair management, and fair representation. One reason the report mentions is that, in South Africa as in most countries, platform workers are considered “independent contractors” and not “employees” and are not regulated by employment and labour laws.

It is, therefore, no wonder that worldwide, platform workers themselves, trade unions and legal writers have been shining a spotlight on this lack of legal protection. In a recent ruling, the UK Supreme Court held that Uber drivers are “workers and not independent contractors. This means that they are afforded some rights and protections under UK employment laws, including holiday pay, rest breaks, the national minimum wage and protection against unlawful discrimination.

How would this change if the workers seen everywhere delivering goods and food, operating taxis and delivering domestic services via commercial platforms were to own the platform themselves?

This question is being addressed by the newly established Centre for the Transformative Regulation of Work (CENTROW) at the University of the Western Cape (UWC). CENTROW’s Domestic worker Co-operative Platform Project (DPCP) aims to build a model for decent work in the platform economy for domestic workers. An international precedent is provided by the domestic worker co-ops, Up and Go and Brightly in New York, where the workers own the platform collectively and determine their own decent working conditions in contrast to companies operating platforms for profit.

Worker co-ops have been seen as an economic alternative that is workable, resilient and exciting, and on the other hand a complex, specialised form of enterprise requiring high levels of internal skill or external technical support to succeed. Worker co-ops are where humanity is placed at the centre of a viable business. DPCP believes that cooperatives could achieve more to advantage poor and vulnerable communities than individuals working by themselves. The International Cooperative Alliance (ICA) defines a cooperative as “people-centred enterprises owned, controlled and run by and for their members to realise their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations.” It enables marginalised workers to create their own work opportunities, on their own terms, using platforms to reach markets that individual workers could not reach.

In 1969, the South African liberation movement decided that after democracy is achieved, the economy would be a three-way system, propelled by a combination of enterprises owned by the state, private individuals and cooperatives “as a tool for facilitating the establishment of community-owned enterprises and worker-owned enterprises”. But in 1994 the reality was very different. The economy was dominated by corporate conglomerates. Registered South African co-operatives were operating along racially divided lines, with state support aligned to the strong, primary white agricultural cooperatives. In contrast, ‘stokvels’ were an age-old form of financial co-operative consisting mainly of women who save money together to pay for family events like funerals and weddings. This type of co-operative was and is based on open and voluntary membership, where the contributors to the ‘stokvel’ control how economic participation and distribution occur. But they fell outside the framework of the law and state support.

Since 2004, the Department of Small Business Development has taken on the task of promoting and developing co-operatives outside commercial agriculture. It introduced a Cooperatives Act in 2005 (amended in 2013), alongside support for emerging co-operatives. With the policy and legislation in place, it is estimated that South Africa had over 48 000 registered co-operatives in 2016 compared to about 4 000 in 2005. However, the mushrooming of co-operatives has seen a failure rate of about 88 per cent and “does not represent a vibrant or coherent co-operative movement”. The Minister for Small Business Development’s 2021/22 Annual Performance Plan promises to finalise and implement a SMMEs and Co-operatives Funding Policy to “improve access to finance and coordinate financial investment of both public and private sector”. But, even if financial support for co-operatives is well thought through, it does not mean that co-ops using platforms will have a chance against transnational platforms like Facebook or Google.

Therefore, apart from considerations about what type of worker-owned entity is most appropriate, there are further important considerations in harnessing the power of the digital economy in the interests of social justice. For instance, data transmission costs are high in South Africa, where the cheapest 1GB of data costs seven times more than Egypt’s cheapest and is three times more expensive than data sold in Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria. Other factors such as access to electricity and costs of hardware like smartphones are a reality. Furthermore, without ordinary people understanding the technology and how platforms operate, things cannot change much in the digital economy.

But this does not mean everyone needs to learn how to code; not everyone needs to be an expert. It is like the difference between a mathematician and people who can calculate things. Workers need to control their own system on open standards and code, even if experts design them. For example, the US CoLab Cooperative assists co-op platforms to co-create simple “purpose-driven web technology”. The aim is to use open standards and codes in a participatory co-design process with workers to create co-op platforms.

The digitally connected population in South Africa is growing. This may alleviate some of the above-mentioned challenges. According to Statistics South Africa, as at January 2021, there were 38.13 million active internet users in South Africa, with almost all using social media and accessing their accounts through mobile phones. In addition, the Platform Cooperativism Consortium at The New School in New York is spearheading a global incubation of platform co-ops with its informative and practical course, “Platform Co-ops Now”. This course is now being run for the third year with CENTROW researchers taking part in this important initiative.

As these examples show, UWC is very much part of the global conversation around platform co-ops and how these could improve the economic situation and livelihoods of the unemployed, the marginalised and the poor by harnessing their initiative and talents.

*Ratula Beukman is a Researcher at the University of Western Cape (UWC).

This article was originally published by the Center For the Transformative Regulation of Work (CENTROW) at UWC.