On 25 May, the Minister of Employment and Labour extended the scope of the UIF’s Covid-19 Temporary Employer-Employee Relief Scheme (C19 TERS) to cover workers who are not registered for UIF. The amendment happened on the eve of an urgent Labour Court application set down for hearing on 28 May, brought by the Casual Workers Advice Office, Women on Farms Project and the Izwi Domestic Workers Alliance.

Lynford Dor, the Media Officer and Educator at the Casual Workers Advice Office, spoke to us about the win for workers and the challenges ahead.

How did you approach the process and what are challenges ahead?

The government passed amendments to the covid-19 Temporary Employer/Employee Relief Scheme (C-19 TERS) directive before the case was heard. These amendments dealt with the last of many demands, which was for non-registered workers to qualify for the scheme. This followed an amendment on 30 April which said that workers could apply directly to the scheme. However, the Department of Employment and Labour/UIF is still yet to open an avenue for individual applications. This has meant that the amendment which opened the scheme to non-registered workers has pretty much been rendered useless. After all, why would an employer who didn’t see the need of registering their workers for UIF now want to apply for the UIF TERS grant on their behalf? The organisations involved in the original challenge might well have to take the legal route once again to push the Department and UIF to roll-out the application process for individual workers.

One of the major lessons we have taken from this process is that the state will use all sorts of legal tricks and threats to delay and exhaust the energies of those who challenge it. All of the numerous amendments to the TERS regulations could have easily been included from day one. The delay to their inclusion has only led to economic and psychological suffering of workers.

I would advise other organisations that are looking to challenge state regulations during this time, especially blatantly irrational and unconstitutional regulations, to be wary of being drawn into endless engagements with government departments and their lawyers – which is their tactic.

How does CWAO approach the law?

Labour legislation in South Africa can be said to have a dual character: it reflects both the victories and defeats of the previous phase of worker struggles under apartheid. Many of the rights that workers have today are the codification of the demands that workers won in those struggles. In the current period, however, with the severe weakening of the workers’ movement, workers find it difficult to access even their most basic rights. The law and its institutions are not immune to the temperature of class struggle, they are influenced by the balance of forces at different moments in history. Workers today are in a situation where they often have to build collective struggles from the ground up to claim the rights that are already rightfully theirs. Recognising this, we look to support workers in building those struggles around their rights in law. But we are also keenly aware that the law, taken as a whole, operates in favour of the bosses’ system of profit-making. So, while we attempt to use the law (i.e. to use workers’ rights) to mobilise and organise workers, we see the law as merely a basis on which to build bigger struggles to advance workers overall interests. That is the theory, at least. In practice, it’s a lot messier.

In terms of the strictly legal side to the law, we also look to litigate to advance worker rights where possible. But even here, work is built off of the organising work that we do with workers. For example, the TERS challenge emerged because we were reasonably well-placed to demonstrate the disastrous effect that the original formulation of the C19 TERS Directive was having on the workers we organise.

How does CWAO choose the legal battles it will fight?

CWAO generally prioritises legal battles that have the potential to set legal precedents that advance the rights of workers in precarious forms of employment, but also more generally to advance worker rights which have a direct bearing on their ability to legally engage in collective struggles.

What aspects of the law are most useful for advancing the interests of precarious workers?

Workers in precarious forms of employment are often mistakenly thought to have no or fewer rights than the old standard of ‘permanent’ workers. The fact, however, is that these workers have rights, they just struggle to access them. So, for example, most of the rights in the BCEA, LRA and OHSA apply to these workers – it’s just a matter of being able to identify what rights are being breached and building worker organisation to fight for them. But again, it is not just what is in the law that can advance workers interests. The task is to assist workers where possible to build collective power so that they can go beyond what is in the law in advancing their interests.

In terms of sections of the law that apply specifically to workers in precarious forms of employment, section 198 of the LRA gives so-called ‘non-standard workers’ like labour broker, fixed-term contract and part-time workers specific rights.

Does the CWAO engage with the CCMA?

A lot of CWAO’s day-to-day work involves assisting workers to take up cases at the CCMA. It does this for two reasons:

- The CCMA is an institution that has come into being as a direct result of worker struggles of the past. It is an institution that is supposed to help workers claim their rights easily and quickly and without workers having to risk the dangers of open conflicts with their employers by going on strike. These are some of the major gains of the previous workers’ movement which should be defended and capitalised upon.

- When workers take up a case to win their labour rights, it can open a space to build organisation and unity between workers. It is also an opportunity to introduce younger workers to struggle and build their capacities for struggle. In other words, CWAO uses the law (or worker rights) as a tool to organise workers to build their power – and not just as an end in itself.

Unfortunately, the other side of the coin is that the CCMA process has become so laden with delays and overly legalistic which often frustrates and depletes workers’ capacity for struggle. Our work constantly has to deal with this contradiction. Curiously, however, the collapse of the CCMA as an effective dispute resolution body also forces workers into the types of direct conflict with employers that the institution was set up to prevent. We ultimately try to support workers in whichever route of struggle they choose – be it through the procedures in the CCMA or more direct forms of power struggles in the workplace.

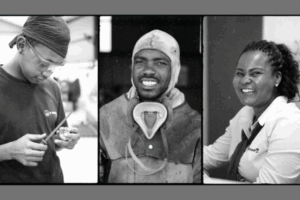

Image: Alaister Russell/The Sunday Times