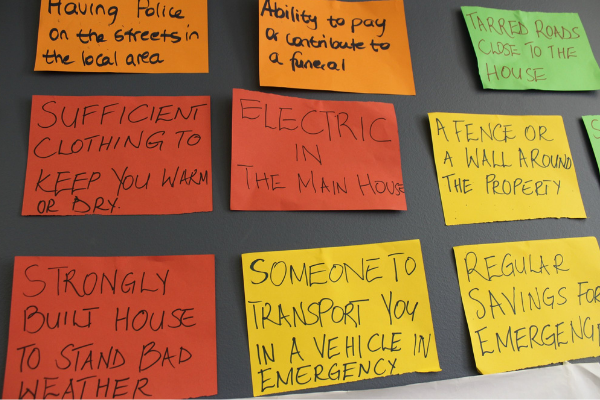

We explained what the decent standard of living (DSL) is – a measure of what ordinary South Africans think are important issues (the 21 “socially perceived necessities”, or SPNs) to enable anyone to live a decent life.

Currently, the middle point of the income of people who have these items is R7,326 per person per month. Why are we so excited about this new measure and how do we think that this can be used to make more effective antipoverty policies? The DSL is so interesting because it provides the diagnostic and gives us ideas of how to beat the symptoms and the impact of poverty in South Africa, by eating the elephant piece by piece.

In this article, we look at the three ways that people can access the SPNs – income, the social wage and community networks. Government has struggled for many years to develop the right policies to beat poverty.

One of the problems of tackling poverty is that it has so many manifestations. Poverty for many is about a lack of money. But being poor also often means you do not have a very secure house, you can’t access the best healthcare and you struggle to send your kids to school. Often, people are isolated when they are poor, as they are not able to put money into the local stokvel or put money in the collection plate at church, and so are not part of the community. Being poor in South Africa is not a choice, nor a punishment meted out because someone is lazy or stupid. Being poor or rich, most largely, depends on where you were born and what support your family could give you, and the kind of education you received. So poverty can be felt in not having money to buy things. Millions of people in South Africa live without a decent income.

Social grants

Social grants are the main form of state-subsidised income transfer in South Africa. Child support grants of R420 per child monthly and older people’s grants of R1,780 monthly are certainly not enough to live a decent life, especially where these grants are the only form of income in a household – but they are a start. The policy of these grants is still based on an apartheid notion of who required income and who would be earning. The grants are targeted at children and older people because of the assumption that (white) adults would be earning wages. Full white employment was almost assured through job reservation policies for white people. This ignores the current reality in which millions of working-age people, mainly black Africans, are not employed. Over 60% of unemployed people in South Africa experience long-term unemployment, with little chance of moving (back) into the labour market. We need a full policy of income grants for working-age people in future, like a basic income grant, but that is another discussion. Even having a job, however, is no guarantee that you will be able to live a decent life. The median income earned by South Africans is only R3,300 per month – we also have a huge number of working poor people in South Africa.

Practicalities

The exciting thing about the DSL practically is that it identifies that there are more ways to live a decent life than just through money, as it identifies SPNs that can be received through the social wage and through social networks.

Social wage

The social wage means services that the state delivers. Even if you don’t have a job, you can access state healthcare and education. These, and social security (grants), shelter and enough food and water are constitutional rights in South Africa. What service delivery protests show is that people are really aware when these rights are not being met through poor state delivery.

Social networks

Social networks are also ways in which people can meet their needs without needing money – so if people require someone to care for them when they are sick, strong communities mean you can rely on your neighbour or family member. The DSL is thus really useful for planners to see linked-up policy development.

Tackling only money poverty is really daunting in a country that has so many poor people. If policymakers can draw on all three ways of eating this elephant, it can be better done with careful planning, sequenced interventions and accountable state delivery. If the DSL is used in this way, we can regularly be celebrating small victories on many fronts rather than facing a problem so big that we don’t know where to begin.

Isobel Frye is the director of the Studies in Poverty and Inequality Institute.

This article was first published by The Citizen.