The expression, “the king is dead, long live the king”, is said to originate in France in the 1400s and was used to indicate to the public that there was a swift continuity from one monarch to the next. The inauguration of the new monarch followed immediately after the death of the reigning monarch. I will use this expression to talk about the living wage campaign in South Africa.

In the popular mind, the living wage campaign in South Africa is associated with the trade union movement broadly, and COSATU in particular. Here is the truth. The living wage campaign is not currently an active or coherent campaign being run by trade unions in South Africa. The living wage campaign is not well defined. The living wage as a set of demands is not well quantified. The organisational report to COSATU’s 12th National Congress confirms that the living wage campaign is limited to the sum of a few parts. The report lists 12 priority campaigns, the first of which is the living wage campaign. In the discussion that follows in that report there is no commentary on the living wage campaign itself, except for a finding in the 2012 Workers’ Survey that the living wage campaign is less well supported than the campaigns around corruption, electricity prices, labour brokers and toll roads. The report to the 13th National Congress confines itself to the national minimum wage, saying that the federation must step up the living wage campaign now that the national minimum wage has been implemented. If you feel that I am picking on COSATU, let us note that no other federation has anything significant to say about the living wage at all.

We know that the living wage is more than just an amount of money, but the living wage campaign sounds like extracts from the freedom charter. It is exceedingly difficult to push this agenda in the industrial relations space only. We know that the national minimum wage is not a living wage, but we have no idea how much a living wage is.

The living wage campaign is dead. Long live the living wage campaign.

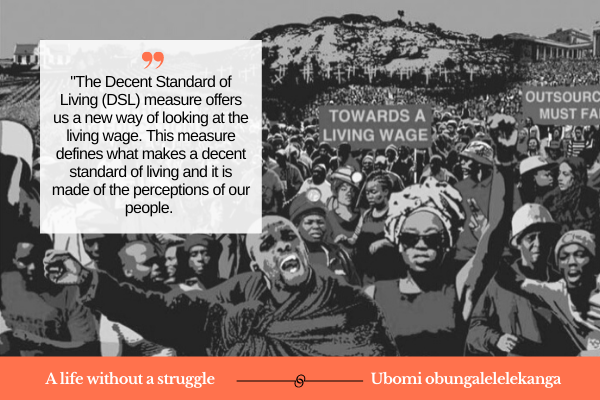

The Decent Standard of Living measure offers us an alternative to minimalist poverty line and survivalist food poverty line measures of the well-being of our people. The Decent Standard of Living measure offers us a new way of looking at the living wage. This measure defines what makes a decent standard of living and it is made of the perceptions of our people. This measure is based on a set of 21 socially perceived necessities for a decent life.

This is what you need to live a decent life, a life without struggle. This is the living wage. Do you have mains electricity in the house, a flush toilet and a fridge? Do you have someone to look after you if you are very ill? Are able to pay or contribute to funerals? Do you have tarred roads close to the house and street lighting? Do you live in a neighbourhood without rubbish in the streets? These are the things that make a decent standard of living.

The per capita income associated with a decent standard life is R7,326 per month in 2019. The monthly salary associated with decent standard of living is R14,242 per month. The national minimum wage is set at R3,500 per month. The national minimum wage is associated with possession of around 15 of the 21 socially perceived necessities. Now we are giving meaning to the numbers. Now we understand what the national minimum wage means for the standard of living of a household. Now we see possible pathways to a decent standard of living. Now we see the different ways our people acquire these necessities. It might be through the purchase of a commodity (such as a fridge), through social networks (someone to talk to when you are feeling upset) or through the social wage (street lighting in your area). Now we can think about ways to help households acquire these necessities. Now we can consider which part of the living wage can be negotiated with employers, with government and with the state. Long live the living wage.

This article was first published by The Citizen.