COVID-19 has caused a significant slowdown in world trade and disrupted global supply chains. South Africa’s geographical position and relative low number of cases has not exempted us from this severe impact. President Cyril Ramaphosa’s announcement of prolonging the national lockdown (from 27 March) a further two weeks (until 30 April 2020) increases the impact on the retail sector.

When trying to make sense of what is happening, or what the impact will be, we speak from a position of inexperience. Retailers are acting on incomplete information, guesswork and fear. We don’t know what the outcome of not only the economic but also the human impact will be, and retailers are scrambling to keep up with disrupted supply chains as well as keeping workers safe during this unprecedented time. This leads to two important questions: Will workers be paid? Will workers be safe?

In terms of cash flow, there has been some relief for retailers during this time. The newly formed retail landlord alliance (known as the Property Industry Group) announced ‘an industry-wide assistance and relief package’ for retail tenants hardest hit by the lockdown. An important requirement of this aid is that retail tenants ‘will need to undertake not to retrench staff during the relief period’.

Retailers expect to be hit hard: Retailer Woolworths expects their profit to fall by around 20% in its financial year end June. Woolworths has pledged to continue to pay staff during the lockdown. Senior Management have pledged to cut their salaries by a third in the next three months to provide additional funds for employees. Given their large salaries, this is hardly a scratch on the surface of the remuneration received by CEOs in South Africa. Ian Moir, CEO of Woolworths, received an annual salary of R18 million in 2019. Should he concede 30% of his salary, this relates to around R450 000 per month.

Africa’s largest retailer Shoprite paid its shop floor and distribution staff an ‘appreciation bonus’ adding up to around R102 million. This amounted to a R700 ‘voucher’ to Shoprite. CEO Pieter Engelbrecht, whose 2019 total remuneration amounted to just over R21 million, said that ‘Our employees are crucial players in the task ahead and the group wants to thank and reward them for their tireless efforts to stock our shelves with food and other essentials for our 29 million shoppers.’ The lowest-paid full-time worker at Shoprite in South Africa receives a pay check of around R4,500 per month (in 2019). Entry-level part-time workers receive around R18 per hour (2019). Shoprite employs over 147,000 people on the continent.

Retail CEOs and other executives are known for big total remuneration packages, the most notorious of which being then Shoprite CEO Whitey Basson who, in 2016, received an annual total remuneration package of over R 100 million. In 2016, CEOs in South Africa were the seventh-most highly paid in the world (ranked by Bloomberg). Per the United Nations rankings in 2017, South Africa ranked 32nd in terms of GDP. In the same year, South Africa ranked 92nd in terms of GDP per capita. This means that large remuneration packages for CEOs and other executives only continue to deepen the disparities of wealth in the country.

This crisis provides an opportune time for retailers to revisit remuneration policies. Covid-19 highlights the importance of workers at the forefront, and it is time for big retailers to recognise that.

In terms of safety, are retailers doing enough? One advantage that South African retailers have is time to react: a privilege many in the Global North did not. President Ramaphosa has bought time with the imposing of the lockdown early on, with a low number of cases. Retailers can look to countries affected by the virus for innovative ideas, and also for warnings. In America, at least four grocery workers have died of the coronavirus.

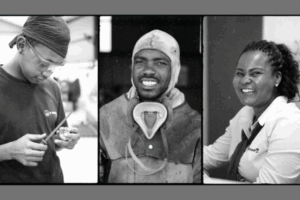

While thousands of workers have been told to stay home, grocery retail workers continue to go to work. Workers report long shifts and extra workloads in order to keep up with demands, and many workers say they don’t have enough protective gear to deal with the hundreds of customers a day.

Two Shoprite stores in Cape Town have had to close after an employee tested positive for the virus. A Pick n Pay store has had to temporarily close under the same circumstances. Those who had worked closely with the infected Shoprite staff members are at home in self isolation for 14 days.

Retailers must plan for the safety of employees while maintaining business operations. How will the workforce be managed under different scenarios? China shows some innovative solutions; some grocery retailers temporarily hired restaurant employees who were out of work due to the lockdown, and other companies moved workers around in order to relieve ‘overworked departments’. Some retailers are equipping their workers with protective equipment, hand sanitiser and putting measures in place to ensure sick workers, or workers who have been in contact with the virus, don’t come to work. But is this enough?